Against the Current, No. 36, January/February 1992

-

1992: Seize the Time!

— The Editors -

Old Nazi in a New Suit

— Scott McLemee -

The Future of Reproductive Freedom

— Angela Hubler -

Women Under Chamorro's Regime

— Barbara Seitz -

Rebel Girl: Women, Sex and Disease--II

— Catherine Sameh - End the Blockade of Cuba!

-

Cornucopia Isn't Consumerism

— Jesse Lemisch and Naomi Weisstein -

Random Shots: Thoughts on Rivethead

— R.F. Kampfer -

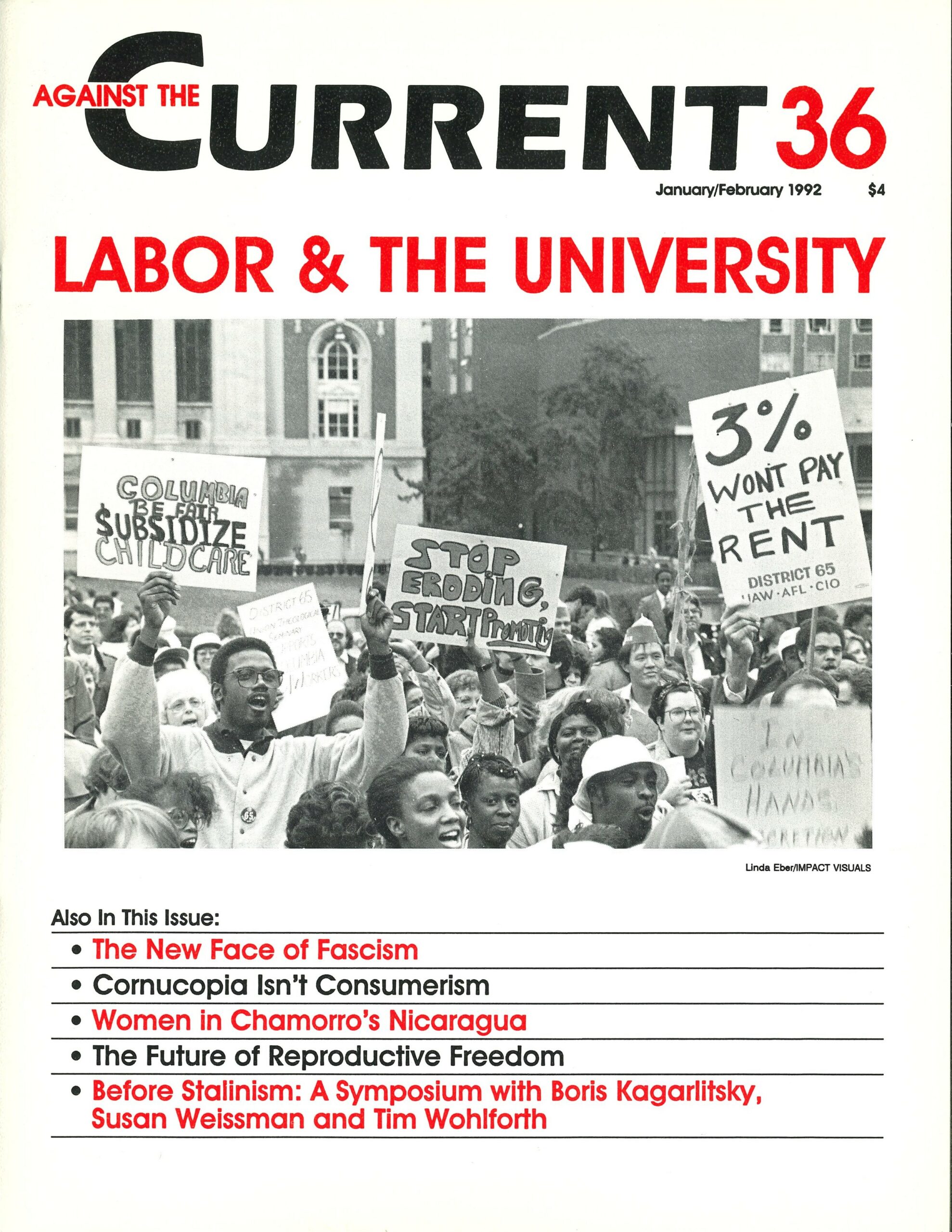

Campus in Crisis Introduction

— The Editors -

Labor and the Fight for Diversity

— Andy Pollack -

From Campus to the Unions

— Nicholas Davidson -

Higher Education on Auction Block

— Phil Cox -

A Proposal to Organize Non-Tenured Faculty

— Tom Johnson -

How to Read Cultural Literacy

— Richard Ohmann -

Introduction to Before Stalinism

— The Editors -

The Onus of Historical Impossibility

— Susan Weissman -

Between the Hammer and the Anvil

— Boris Kagarlitsky -

In The Grip of Leninism

— Tim Wohlforth -

Dialogue: On the Soviet Upheaval

— Ellen Poteet -

On the End of Stalinism

— David Finkel -

Bette Midler's "For the Boys"

— Nora Ruth Roberts

Catherine Sameh

NOTHING HAS COME to represent the U.S. social crisis quite as vividly as AIDS. The word conjures up not only images of individuals dealing with illness, but major urban centers in rapid decay and social institutions unraveling at the seams. The extent to which illness operates as metaphor in this country has only been furthered with the dawning of this new and puzzling disease—perceived as a disease with no cure insight in a society with no sure future.

For centuries, life-threatening diseases have been steeped in harmful metaphors that serve to isolate them and their victims from the “healthy” rest of the world. Those with these diseases have then been blamed for “acquiring” their disease The very word “acquire” creates the image of people seeking out disease, as if to add to their private collection.

Sexually transmitted diseases come specially packaged in extra guilt, given the fact that sexual contact is not only a choice in behavior, but is the most “indulgent” behavior there is.

Women with AIDS in this country are shrouded in a heap of metaphors and blame, while their need for adequate health care continues to be denied. With the rate of AIDS contraction rising among women, they face increasing punishment, in the form of lack of information and services, for being sexual. With our government’s usual victim-blaming approach, women with AIDS are told to change their lives, their behavior and their desires.

Certainly life-saving behavior should be promoted. Recent alarming statistics illustrate the extent to which women need outreach about HIV: The average number of sexual encounters a year foryoung women and men aged sixteeen was six and nine respectively; HIV is now one of the top five killers of women aged 14-34; one in three HIV-positive women will give birth to an HIV-positive child.

These statistics necessitate very urgent responses. But just as cancer won’t be eliminated when people cut fat from their diets—which will only help along a more comprehensive process—women and girls should learn how to be safe without having to deny their sexuality.

Magic Johnson has dramatically heightened public awareness of HIV contraction among heterosexuals. But his brave step forward, though largely positive, has its problematic elements. The search is now on for the mysterious woman who gave the virus to Magic, fuelling the public’s willingness to blame women for the virus.

And as Martina Navratilova pointed out—were she to go public if she found out she were HIV-positive–as a woman and a lesbian, she would probably be harassed and stigmatized instead of being treated as a hero.

It’s as if, having fought so long for better, freer and more frequent sex, women are now supposed to be sorry for pushing so hard. There is almost a that’s what-you-get attitude in both public and private responses to women with AIDS that can be traced back to the roots of metaphoric thinking about disease and to conservative notions about women’s sexuality.

After working with cancer patients for over a year, I still find myself occasionally assigning blame where blame is not due—to patients themselves, searching for the tragically poetic reason they are sick, ascribing certain mythic explanations to diseased organs. And when I worry about my own body immersed in a diseased world, I know I am wading through swamps of metaphors about what I “deserve” and what is “inevitable” because I am a woman trying to make sense of my sexual life.

But sexual life in this period is largely nonsensical. We are all steeped in metaphors that we have inherited and adopted as normal. We are vulnerable to the strength of these notions and therefore passive receptors of them.

If women are to get the resources and dignity they need when facing serious diseases like AIDS, we must explode the metaphors that haunt our society about illness and sexuality and lead only to a politics of neglect and blame.

January-February 1992, ATC 36