Against the Current, No. 35, November/December 1991

-

PC-Bashing: A Vicious Frame-up

— The Editors -

The New Russian Revolution?

— The Editors -

The Crisis of the Campuses

— The Editors -

Multiculturalism As It Really Is

— The U-T Writing Group -

CUNY's Springtime of Struggle

— Anthony Marcus -

Multiculturalism in Brooklyn College

— Nancy Romer -

Campus Unionism at Twenty Five

— Milton Fisk -

PC: A New McCarthyism?

— Ellen Schrecker -

Wasted Minds and Wasted Lives

— Jake Ryan and Charles Sackrey -

Review: The Right's PC Frameup

— Mike Fischer -

Viewing "Berkeley in the '60s"

— Mike Parker - Three Views of the University

-

Russia: Toward a Party of Labor

— David Finkel -

Russia: A Fast Walk to Nowhere

— I. Malyarov -

Poland's Crisis and Solidarity Today

— Mark M. Hager -

Jan Josef Lipski

— David Finkel -

Puerto Rico's Albizu Campos Centenary

— Héctor Meléndez -

C.L.R. James: Intellectual Legacies

— Kent Worcester -

Random Shots: The East Is Read

— R.F. Kampfer -

The Rebel Girl: Women, Sex and Desire

— Catherine Sameh -

Anita Hill--and Ourselves

— Dianne Feeley

Mike Parker

“Whoever thought the ’60s would be called the good old days?”(1)

I LEAVE TO others the questions of production values and art of Berkeley in the ’60s. The massive work that evidently went into collecting materials and the participation of leading ’60s Berkeley activists will likely make this impressive film the popular left historical record for the decade’s political movements.

Unfortunately, despite many good moments, the film distorts the political developments of the ’60s because it doesn’t quite understand them. Subtly, if unintentionally, it reinforces today’s defeatism, political confusion and marginalization of the left.

The most important question is whether viewers leave the film feeling

1) the exhilaration of mass movement power;

2) the generosity, self-sacrifice, full-scale commitment and social consciousness generated by movements sweeping “Selfishness is human nature” theories into the dust bin;

3) the intellectual excitement of people rethinking basic beliefs; the marvel at how even conservatives following democratic values through to their logical conclusions can become revolutionaries in a matter of months;

Or does the film leave a bitter aftertaste by implying that even the cleanest, purest political activity will likely develop into political craziness and degeneracy?

If you respond to the whole film by celebrating the ’60s political activism, it is probably because your own politics and commitment are strong enough to filter out the elements that tilt the film toward • message of defeatism.

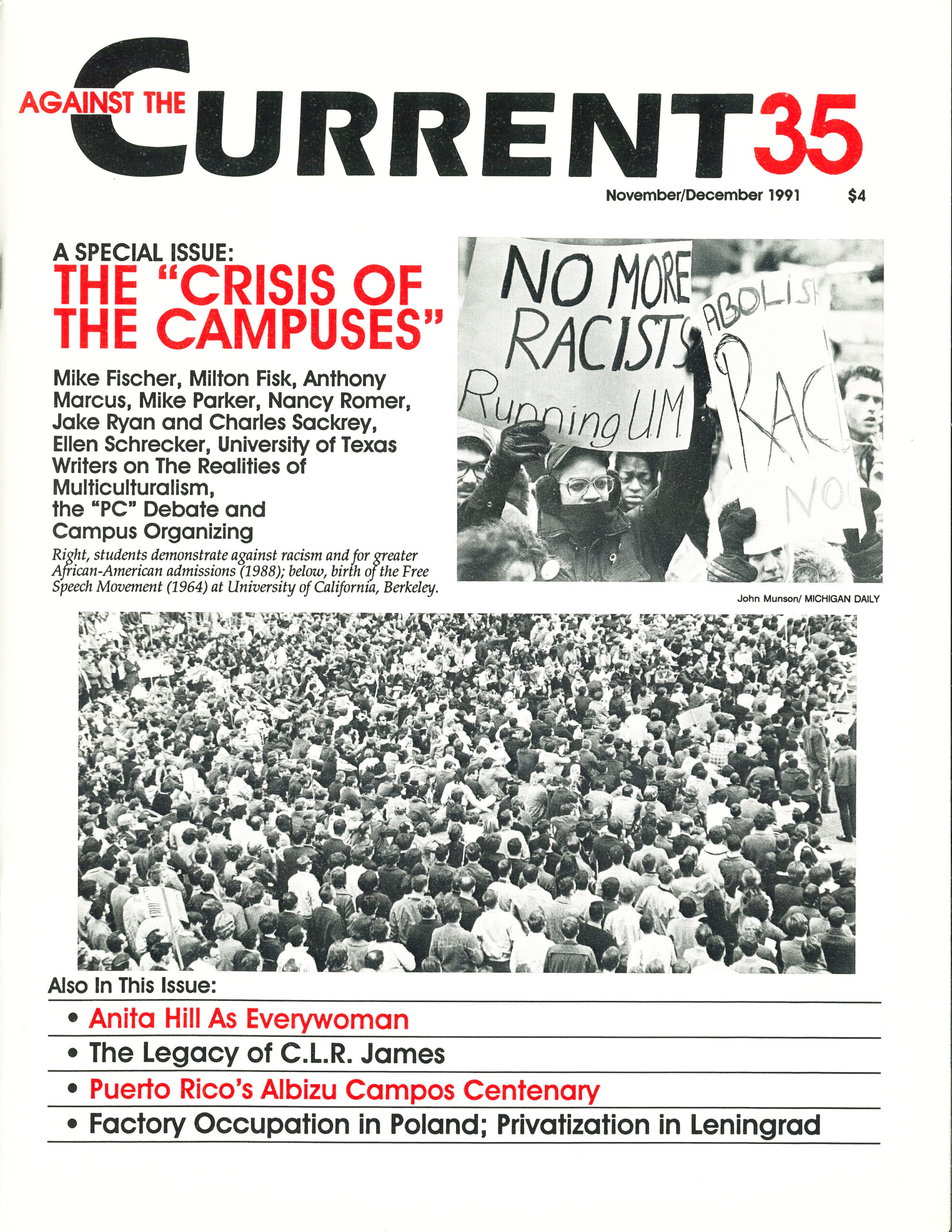

Producer/Director Mark Kitchell was a Berkeley High school student when the Free Speech Movement (FSM) erupted on the University of California campus. He tells the story through film clips from the period interspersed with reflections by fourteen older and wiser’60s Berkeley activists including Jack Weinberg, Jackie Goldberg, Frank Bardacke, Bobby Seale, and David Hilliard.

Reliving the Period

The clips offer some wonderful glimpses into the period. At times you can feel the movement building in the craziness of the surrounding world. Ronald Reagan’s campaign denunciation of a degenerate Berkeley dance speaks volumes about the mentality of the right University President Clark Ken’s description of the knowledge factory provides the liberal context And FSM leader Mario Savio’s ability to articulate the morality and principle of a mass movement causes tears of pride to well up.

Kitchell’s topic is hard to capture in one film. For us everything was related so the movement was about everything. Particularly after the FSM victory we felt we could change anything if we set our minds to it We felt real -empowerment–not like today’s jargon which more often means believing you are choosing what you are in fact forced to do.

As a result we felt free to experiment at all levels from personal relationships and alternatives to the nuclear family to different forms of education, art, economic enterprise and community organization. We could take on the administration, the federal government, the power structure, the establishment, capitalism, Communism, racism, sexism, our own personal histories, our own minds and perhaps a few physical and biological laws.

Obviously one film can’t cover everything. Kitchell focuses mainly on the battle against the House Un-American Activities Committee, the fair employment struggle against San Francisco hotels, the Berkeley campus Free Speech Movement, the Black Panther Party, hippies, Women’s Liberation and People’s Park He has avoided throwing in every sensationalist clip and rightly leaves out what the reactionaries dubbed the brief “filthy speech movement,” the Sexual Freedom League, and some of the seamier aspects of the drug culture.

The film is at its best covering the FSM where the lines were sharp: the “great middle” virtually all went over to the good guys to decisively defeat the forces of evil. The roots of the FSM in the civil rights movement are clear. Kitchell succeeds in providing the sense of how a mass movement is not mob psychology but rather huge numbers of individual choices which underlie the transformation from unsure, hesitant observers to committed partisans.

What is obscured is the critical role that the socialist organizations played in making possible the rapid intellectual and organizational growth of the FSM. The independent Socialist Club’s pamphlet The Mind of Clark Kerr by Hal Draper was widely read and acknowledged for its exposure of the university’s phony neutrality and analysis of the university’s subordination to social power.

Socialist groups also provided critical organizational and political knowledge and cadres. These were not counter to, but in synergy with, the dynamism and imaginative ideas brought by the thousands of new people drawn into the movement.

Breaking Down Divisions

Senator Joe McCarthy had been politically destroyed in the ’50s, but not McCarthyism. Socialists and Communists were automatically suspect Only political activities of Independent? or even people without a political thought in their head were “genuine.”

Breaking down this divisive fence within the movement was one liberating part of the FSM. There was openness about socialist and communist participation. Their contributions and experience were valued, and their ideas were challenged and debated.

Kitchell and most of the commentators hide the socialist groups’ role partly because they don’t understand it and partly to protect the purity of the FSM experience. But in so doing they reinforce this hangover from McCarthyism which is still consciously used by capitalist ideologues and trade union bureaucrats to marginalize and isolate the left.

It is not true that the FSM was simply regular patriotic Americans who wanted nothing more than to see the Bill of Rights upheld. There were many like that—but also many in the leadership and rank and file who had already come to the conclusion through struggle and study that these goals were frauds under capitalism, and that the entire system had to be fought and changed in order to win the rights that capitalism promised.

It did not mean that we were any less committed to free speech or the struggle for it. It was that we understood how far we would have to go to truly win.(2)

History Obscured

The absence of political groups from the story also makes it virtually impossible to understand what the FSM and subsequent movements really produced; the film subtly ends up providing the ’80s liberal interpretation of history.

Two tendencies emerge from the FSM: the hippies and the politicals. The hippies tried to build new kinds of relationships and a new society within the old by ignoring its power. The politicals understood that oppressive society and its values, oppression and war could not be ignored—movements had to oppose and change it.

The film portrays both approaches as leading to irrelevance, the result of acting out fantasies. The significance of Oakland Stop the Draft Week (STDW)—.a series of planned disruptions of the military induction center—is explained by one or two of the commentators.

STDW was a statement that a movement had been built which would escalate the social cost of continuing the war. That movement forced an incumbent U.S. president, elected by a landslide, out of the 1968 presidential race partly by making clear that every campaign stop required a wall of thousands of police.

But this message is lost in the preponderance of voice-overs and editing which give the impression that STDW, while exciting, hurt the innocent and was mindless and ineffective because it failed to stop one inductee.

The film reinforces this dead-end image by moving immediately to the negative portrayal of the Panthers and disproportional focus on the poorly conceived Peoples’ Park activities.

With the exception of a couple of militant antiwar demonstrations, most of the activities of the political trend developed from the base of the FSM are missing from the film. There is no mention of the near victorious Bob Scheer Democratic Party primary campaign on a radical antiwar platform against a strong liberal-labor pro-war mainstream Democrat and the debate about that strategy.

The film ignores the broad Bay Area antiwar movement, which involved hundreds of thousands in demonstrations. It misses the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) projects, the CORE campaigns against employment discrimination, the Farmworkers struggle, and the community political campaigns. It misses the Peace and Freedom Party which, against all predictions, succeeded in registering more than 100,000 Californians in a new political party and became a catalyst for third-party developments in other states.

It’s not that some of my favorite struggles were left out The film focusses on some explosive events while missing the core of the Berkeley movement, the hard-working dedicated people who never got the attention they deserved from an establishment media looking only for sensationalism. This partly explains why the section on the development of women’s liberation seems so disconnected from the rest of the film.

The film also misses the development of thousands, of serious socialists who became committed organizers in community and working class struggles in the ’71k The only hint of this is contained in the where-are-they-now notes on the commentators at the end of the film.

Had world events taken a different turn in the ’70s, had the cracks in capitalism widened, and had Communism collapsed twenty years earlier, then many of the ’60s trained radicals would have become leaders in new mass movements. Berkeley in the ’60s might have been analyzed for its significant contribution to sweeping changes in America in the ‘70s. Instead we were swimming in a strong rightward stream. Many did not survive politically and others chose to ride the current.

Getting the Panthers Wrong

The worst part of the film is the collection of commentaries which suggest that the Black Panther Party’s explosive growth was simply a media creation combined with the Panther ability to con would-be white revolutionaries. There is some truth in both these points but they are completely wrong as an explanation.

Understanding this requires a little context. By the mid-1960s the civil rights movement had come up against its own limitations and those of welfare-capitalist America. The tactic most effective in confronting the legal discrimination in the South—the appeal to conscience and fair play that marked the non-violent civil right movement—had little effect in challenging the problems of the North.

The few victories were important as symbols but did not change the racism institutionalized in economic relations. The civil rights movement which had the passive support of most Blacks was unable to mobilize cadres in the ghettos. Martin Luther King tried to organize Chicago and failed.

The civil rights movement couldn’t change the conditions and it couldn’t tap the ghetto anger starkly expressed in the series of major urban riots usually triggered by police brutality.

Nationalist groups did have an impact. Most prominent were the Muslims whose program amounted to a religious, separatist, Black capitalism. In not confronting capitalism, the Nationalists were tolerated by it. But within the Nationalists tendencies emerged which began seeing the capitalist system as the enemy and began looking for white allies. Malcolm X moved in this direction.

The Panthers also represented this tendency and were able to relate to and organize ghetto anger into a movement. The visual images contradict the commentaries in the film and show the Panther seriousness and numbers. And Panther influence went far beyond this.

Black berets and pride moved into the Bay Area schools as students maintained order, and insisted that education was critical to the African-American community. The Panthers, like the Muslims, had some success in helping addicts beat drugs and in motivating school dropouts to learn math and reading so they could distribute and read the Black Panther newspaper and play a larger part in the movement.

The Panthers were able to use the media to spread their message but it was the politics of the Panthers that caught on and made the Panthers the group to be reckoned with in city after city. The key to the Panthers’ organizing success was asserting the right to self-defense in addition to the traditional civil rights demands for social justice. Like the FSM, the Panthers were built by insisting on actualizing a right embedded in principle in American tradition and law.

An Alliance and Its Demise

Did the Panthers ever con white radicals for money and support (what some have seen as the film’s big revelation)? Sometimes. But this was not central to the Panthers during their ascendancy, and conning whites was not a Panther invention. In some ways it was a logical extension of the last phases of the civil rights movement where some African-American leaders did nothing but organize white liberal support. As the Black Power slogan developed some white-oriented Blacks made a career out of playing on white guilt.

In this context it was the Panthers who represented big advances in the way Black Power related to white movements. At the very beginning their program was formulated and articulated to mobilize a core in the African-American community, regardless of what whites thought. At the same time they developed an understanding of the need for working with whites and made great strides in developing the formula for doing so out of the requirements of real political struggles.

When Huey Newton was arrested on murder charges and the Panthers needed white support they sought, agreed to and worked on a coalition arrangement initially with the California Peace and Freedom Party. The Panthers put out Kathleen Cleaver’s sharp analysis on the self-defeating relationship between the African-American community and the Democratic Party and the role of Black politicians.

The coalition was not easy to sell for either side and extensive education work had to be done. In the Peace and Freedom Party we had to win people to the notion of “Free Huey” rather than “Fair Trial” by winning people to an understanding that at issue was not a narrow set of facts as in a regular trial but the social and political context which made this a political trial.

The Panthers were up against a social order committed to wiping them out Their already thin leadership was disoriented, divided, and killed by federal and local agent-provocateurs and murderous police raids.

The Panthers were moving rapidly to challenge capitalism at the same time that possible domestic allies were puffing back The antiwar movement was self-destructing by once again looking for a Democratic Party savior. The white trade union leadership smashed the militant Black movement in the UAW while absorbing some of its leaders.

As the Panthers became more isolated and desperate their political mistakes compounded. Panther politics became perverse—latching onto antifeminism, Stalinism, Yippeeism, gangsterism and terrorism—and quickly they were destroyed.

But the Panther experience, though compressed in a couple of years, was as genuine and as important as the Free Speech Movement was for the elite students at Berkeley. The main difference is that many of the elite students went on to positions of power and money where they could influence their own official history to preserve the purity of their early experience.

Notes

- From “They All Sang Bread and Roses” by Si Kahn, Sung by Ronnie Gilbert.

back to text - The best description and analysis of the Free Speech Movement is Hal Draper, Berkeley: The New Student Revolt, Introduction by Mario Savio, Grove Press, 1965.

back to text

November-December 1991, ATC 35