Against the Current, No. 27, July/August 1990

-

A Non-Peace Non-Dividend?

— The Editors -

Black Workers for Justice

— an interview with Nathanette Mayo -

Building from the Grassroots

— Cynthia Bowens -

U.S.C. Out of South Africa

— Harry Brighouse, John Hayes and Michele Milner -

Abortion Pill Is No Panacea

— Joan Batista -

RU 486 Is in the Spotlight

— Joan Batista -

Ford Battles Mexican Workers

— Dianne Feeley -

Soviet Jewish Immigration: Gift or a Time Bomb?

— Michel Warshawski -

The Cancer Epidemic, Part I

— James Morton -

Tracking the Rise of an Epidemic

— James Morton -

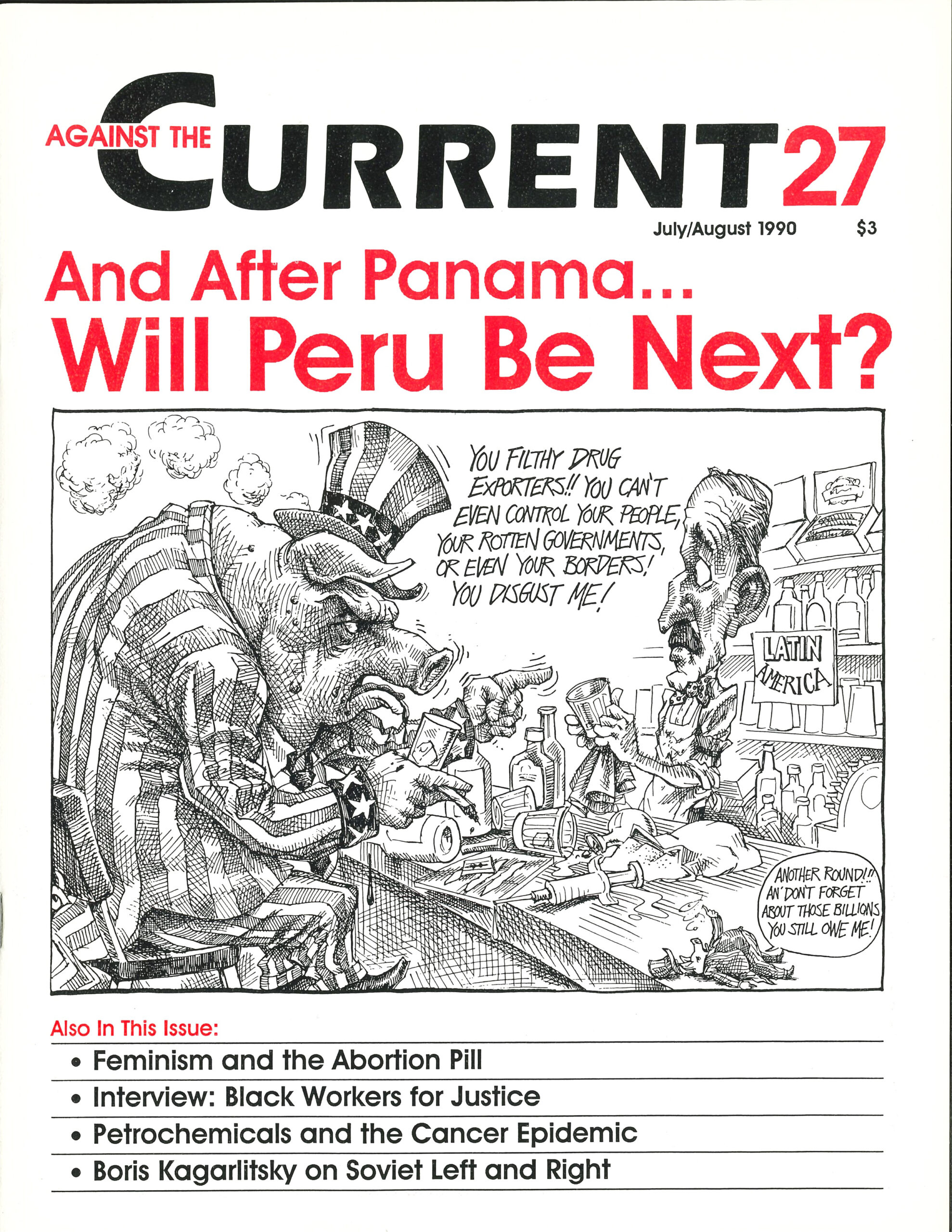

Drug Wars and the Empire

— Peter Drucker -

Mujahideen and Dealers

— Peter Drucker -

The Meaning of the Puerto Rican Plebiscite

— The Taller de Formación Política (TFP) -

Soviet Struggle: What is "Left" and "Right"?

— Boris Kagarlitsky -

Dialogue: The Third World After the Cold War

— James Petras and Mike Fischer -

The Afghans' Tragic Drama

— Val Moghadam -

Afghan: Socialism from Above and Outside

— Samuel Farber -

Random Shots: Summertime Musings

— R.F. Kampfer

Boris Kagarlitsky

“WE MUST REPULSE the forces of the right,” decisively proclaims an orator at a meeting of the People’s Front in Luzhniki (near Moscow). A country writer complains that the press has begun an incomprehensible lean toward the left “We are pressured from the right or from the left, but we will firmly follow our course,” a state leader solemnly assures his audience.

Within the context of the sharpening political struggle, the concepts of “right” and “left” have become an inextricable part of our daily life. They are used everywhere, appropriately and inappropriately. Sometimes, in samizdat journals, attempts are made to define these terms. For example, in Nevsky Notes (no. 5, 1989) Dmitry Shubin categorically declares that the Western “left” “is utterly not the same as ours” and that analogies are simply out of place. A Polish public figure—a former dissident who is now a deputy in the Sejm (Polish Parliament)—Adam Michnilç persistently demands that the terms “left” and “right” be completely abandoned, for they contradict the reality of Eastern Europe.

But this is not so easy! Language lives according to its own laws. What is it then that compels us again and again to use these terms, which seem to have come to us from a “foreign” political civilization and from a different epoch?

Actually, difficulties with political concepts have arisen not only for us and not only in our times. In a book by American journalist Anthony Sampson, The New Anatomy of Britain (New York, 1972 Moscow, 1975), I came across the following passage (53):

“From the English point of view it has always been difficult to tell who is the left. This term, in essence, is connected with the continental conception, tracing its beginning from the French People’s Convention of 1789. The concept of ‘the left’ began to spread in England only from the beginning of this century, and it could never be wholly attributed to the Labor Party. Not a few efforts have been made to show the difference between the left and the right. Here are some of the definitions which from time to time are used for their characterization:

| LEFT | RIGHT |

|---|---|

| the People’s control of the means of production | private enterprise |

| changes | traditions |

| equality | elitism |

| compassion | cruelty |

| tolerance | discipline |

| “doves” | “hawks” |

| democracy | aristocracy |

| state regulation | freedom of private initiative |

From my point of view, three components are missing in such a clarification. First, in the 20th century the left has traditionally proclaimed socialism as its ideology (although interpretations of the socialist idea may be quite different). Second, the characteristically notable feature of the Western left has always been the struggle for the democratic participation of workers in the management of the economy. In other words, at stake is a challenge to the rights of the privateer, whether it is the private firm or the state. In both cases democratization means the inescapable restriction of the rights of property.

Naturally, not only left parties have used the term socialism. During the 1930s and 1940s, it was fashionable to say that “we are all socialists now” in certain circles in the West Both liberals and fascists flirted with socialist terminology, as did populist leaders of Latin America (whose bourgeois character one can hardly doubt).

However abused, the ideology of the left always presupposed a conception of socialism that invariably included the primacy of society over the state, firm social guarantees for the workers—guarantees, not handouts granted by the magnanimity of generous rulers—and workplace democracy.

From this point of view Stalinism always fit poorly into the traditions of the left. At one time the Stalinist ideologues completely avoided the use of the term “left,” though in the periods of the United Front and the Union of the Left Forces, when it was necessary to unite with socialists, they proclaimed themselves to be part of the “left camp.” These ideological problems reflected the internal contradiction of Stalinism, which was struggling with “limited bourgeois democracy” in the name of the workers while simultaneously denying democratic rights to the workers themselves.

Third, “the left” are those who are on the side of the workers against the ruling classes and oligarchies. This circumstance predetermines all the rest. If one has difficulty telling “who is left and who is right,” the movement of the masses themselves has not yet matured. This means, above all, that the arrangement of class forces in society is not yet crystallized.

Yet let us return to Mr. Sampson. The 1960s, he writes, brought confusion “into the definition of what must be considered left” (54). Both major parties in Britain held similar views on the fundamental questions of people’s life Compromise prevailed in society. Alas, the words written by the American journalist about Britain of the 1960s and 1970s cannot be attributed to the 1980s.

With Thatcher’s ascendancy, no one can have doubts any longer about the difference between the left and the right A polarization of forces took place; the struggling poles clearly defined their positions. The reforms of the conservative government, in carrying out a radical rightward course, caused a corresponding leftward shift of the opposition. As the battle between the government and the miners during the strike in 1984 showed, what is at stake are vital class interests and not merely detached ideals.

If, even in England, with its ancient political culture, there has been confusion over what is “left” and “right,” it is easy to guess how much confusion surrounds this term in our Russian minds after the totalitarian experiment conducted on us. By definition, a totalitarian regime can be neither right nor left It always occupies the position of “common interest” and the “greatest benefit.”

A totalitarian regime does not occupy some part of the political spectrum because it replaces the entire spectrum with itself. Its logic is the logic of global balance. If somewhere there arose a “rightward” leaning, then for the sake of symmetry a “leftward” one must also be discovered and destroyed. The logic of totalitarian rule is encapsulated by the prison camp wisdom: “A step to the left or step to the right is considered escape. The guards shoot without warning!”

Obviously a totalitarian regime may use “left” or “right” terminology, depending on which “”works” better in a given situation. As a rule, though, the language of totalitarianism is mixed. Stalin staged himself as both the heir of the revolution and embodiment of the idea of Russian statehood. He invoked proletarian principles and insisted on patriotic priorities, proudly proclaiming revenge for the defeat of the Russian Empire by Japan.

Under totalitarian conditions there could be no room for opposition, and therefore there was no place for politics as a competition of various political groupings. Concepts of “right” or “left” acquire meaning only when political struggle emerges—when the most elementary conditions for political pluralism arise. So it is only in the 1960s that a civil society in our country began to emerge–w here currents not already controlled by the authorities began to develop. And, not accidentally, it was then that we begin to talk about the “left” and “the “right.”

Throughout the 1980s political life has been in the process of thawing itself out Almost out of nowhere there appeared the most varied groupings, from anarcho-syndicalists to monarchists. And, naturally, confusion began.

It is characteristic that in different cultures the terms “left” and “right” seem to carry different emotional charges, In France, the right are not ashamed to call themselves right In Russia, on the contrary, it is precisely the term “left” that appears especially attractive. The left stands against authority, itself a great benefit in a country that has not known political freedoms.

It does not follow from this, however, that any opposition is to be considered left. A large proportion of the popular critics comprising the core of the Moscow—and then inter-regional–deputy group (in Parliament) by no means fits the definition of “left.” Their position is classically liberal. In the spectrum of today’s political life they dearly represent the center. The fact that liberals count themselves among “the left” is in itself not new for Russia; the situation was exactly the same with the Constitutional-Democratic (Cadet) party during the 1905 revolution. Many slogans sound very radical, but in looking more carefully at the programs and political practices of the Russian liberals, it is easy to find that very little has changed during the last eighty-odd years.

The demand to transfer everything possible into private hands, or to replace planning by market relations everywhere, in no way undermines the positions of the ruling circles. At stake is only the redistribution of power and privilege inside the ruling circle. For the mass of the population, who are allowed the role of wage workers, such changes will improve little. It may be argued whether the proposed market reforms will increase the effectiveness of the economy as a whole—the experience of Yugoslavia, Hungary and Poland shows that in the conditions of structural crisis such a policy does not necessarily bring any benefits.

Nevertheless it is clear that the liberal strategy will inescapably lead to the rapid deterioration of the already far from remarkable conditions of the poorest part of the population. Proponents of reform speak quite candidly about the intensifying exploitation of workers and the reappearance of unemployment. The enrichment of a small portion of the “dynamic people” is already visible. The prospect is clear: power is exchanged for money, money for power. From society’s point of view, “illegitimate” bureaucratic privileges are replaced by “legitimate” privileges—those bought or “earned.”

In an obvious way, the freedom of private initiative becomes the freedom for those who have money. And who has money in today’s society? Those very privileged layers that are so loudly denounced by our fashionable critics: the apparatchiks, the mafia, their relatives and those who are close to them.

The restoration of capitalism, which so frightens the zealots of totalitarian virtuousness, is not really at stake. Even with the greatest possible desire to do this these social layers cannot build a “developed capitalism” in our country.

Civilized capitalism is possible only with the existence of a civilized bourgeoisie, which it took the West more than three hundred years to form. One can talk as long as one likes about prosperous life in Sweden and one can repeat the Leninist quote about socialism being a social order of “civilized cooperators” an endless number of times, but from this our “cooperators”(1) will not become civilized en masse. And Soviet economy will not resemble the Scandinavian one.

Some number of advanced cooperatives, aspiring to the incorporation of new technologies, organized by democratic principles and conscious of their responsibility to society, cannot qualitatively change the situation, but only once again reveal the barbarity and anti-democratization of the rest.

Under the real conditions of our country, the “inoculation” of capitalist methods means the restructuring of relations within the privileged minority, thus preserving the main features of the system. This course is not very compatible with democracy. As the first experience of the cooperatives demonstrates, the overwhelming majority of the population is not overly thrilled about them. In fact, they demand their closing. It is not difficult to guess what will become of the liberal economic reforms if their fate should become dependent on the will of the majority.

Precisely this circumstance explains the inconsistency and timidity of liberals on political questions. They insist on greater freedoms, but do not dare to take a stand on the role of opposition. They criticize the government on the particular, but do not wish to offer alternatives. They are for free trade unions in theory, but call for the abandonment of strikes in practice. They are for transferring the decision-making process on all questions into the “parliamentary” organs of the Supreme Soviet, which they themselves have recently called “Stalinist-Brezhnevist.”

In reality, the existing semi-democratic organizations and procedures correspond best to the liberal project. Efforts are made to perfect them, to rationalize them, but not to replace them by new and democratic processes Recently there have appeared those who openly advocate installing a strong authoritarian regime to insure the success of the reforms. Andranik Migranyan and Igor Klyamkin have become the chief ideologues of “enlightened authoritarianism” among the liberal public.

When Migranyan and Klyamkin say in the pages of Litaraturnaya Gazeta that the reforms they propose will not be accepted by the people and cannot be realized without a “strong hand,” they are perfectly right. But at the same time, they do not dare admit that the anti-popular and anti-democratic character of their position completely reproduces the traditional Stalinist schema. That is, for the benefit of the people and of democracy the rights of the people must be restricted. In these new conditions, market Stalinism appears as the natural continuation and development of “classical” Stalinism.

History thus repeats itself. Liberals at the end of this century act in relation to the system which has emerged in exactly the same way as liberals in the past reacted to tzarism. This similarity becomes even more striking because the conservatives of these two periods differ significantly from one another. While in both cases the conservative forces relied on the state bureaucracy, in the old Russia there existed a landed nobility and a substantial bourgeoisie. Today’s conservatives are clearly foreign to the bourgeois world view. They invoke proletarian values, although real movements of the masses are perceived by them as “revolt” and an “intolerable deterioration of discipline.”

Yet it must be remembered that the “classical” Russian liberals were en masse not bourgeois. They were, above all, the privileged, elitist intelligentsia, a part of the management apparatus of industry and the enlightened portion of the officialdom. They were, in other words, the very layers comprising the base of support of current liberalism. Then—as now—they saw that within the context of Western society the position of their colleagues is significantly more solid.

Not being capitalists themselves—and not about to undertake the practical task of “the building of capitalism”—those earlier liberals dreamed of the country’s transition to a Western path of development. But, in the absence of a developed bourgeois class, this transition could be facilitated only by a power that would enforce new social relations from above through methods that were far from democratic.

The difference between the liberalism of those times and the current situation consists only in that at the beginning of the century there was at least a small grouping of civilized bourgeoisie, while today there are only cooperators and mafiosos—who are not civilized.

The necessary component of the liberal project, Chen and now, was the existence of a firm power capable of carrying out transformations. Here the Russian liberal has always found common language with the conservative. But due to the current conservatives’ changed social base, they are not very receptive to the Western path. Ideological workers(2) disillusioned with perestroika have already begun to organize United Fronts of Labor, attempting to find support from workers. These elements proclaim themselves to be the opposition and seek to occupy the political space where, logically, the left must be located.

Alas, the United Fronts, with their thundering mix of revolutionary rhetoric, anti-democratization, and hatred toward any change, cannot offer the masses an attractive prospect of social development. Hence they cannot become a realistic alternative. Neither can they become a real threat, for they represent the conservatism of yesterday. Intelligent and competent conservatives have long opted for market Stalinism. Cumbersome and poorly oriented in the changing conditions, United Fronts of Workers can in no way compete with the “informal” organizations, which have acquired considerable political experience during the 1987-89 period.

In general, the recently emerging non-official organizations span the richest political spectrum. It is exactly here that we will find the greater part of the left wing. Yet one should not be taken in by illusions. The experience of non-formal organizations shows that many of the groups who are unquestionably radical are by no means left.

As in the West, the concepts “radicalism” and “conservatism” are far from coinciding with “left” and “right.” For example, the British Labor Party, despite an indisputable adherence to the values of the left, has shown astonishing conservatism and a complete inability to initiate change. This predetermined the catastrophic defeat in 1979, from which British socialism has still not recovered. At the very time that the left was becoming more and more conservative and pragmatic, the right was radicalizing. The Thatcher government has proven to be one of the most radical in postwar Britain—and the most rightwing.

Returning to native soil, the Democratic Union (DS) is more radical than the Moscow or the Yagoslav People’s Front (NF). Yet in its program and ideology the DS is a party of the right, inspired by the values of free enterprise and free competition. (For a DSer, the belief in an ideal society, purportedly already built in the West, is as unshakable as was the Western Stalinist-Communist’s belief in Red Russia in the 1930s.)

On the other hand, the People’s Fronts of Russia, having raised the banner of self-government, may undoubtedly be attributed to the left camp, although this movement too is far from homogeneous.

Inside every political grouping there emerges “moderates” and “radicals.” Psychologically they may have a great deal in common, although their ideological positions will be incompatible. It is characteristic that the most radical members of the Moscow NE as likewise the activists of DS, are inclined toward confrontation with the authorities. They go out and demonstrate on any occasion. But ideologically the NF radicals stand furthest from the leaders of DS: as a rule they have socialist ideas, and are often Marxists. It is sufficient to compare the newspaper of the radical wing of the MNF, Our Cause, with an edition of the DS paper Free Word, to see the incompatibility of these two types of radicalism.

On the whole, the following schematic illustrates the correspondence of radicalism and conservatism:

| conservatives | ||

| moderates | ||

| left | right | |

| liberals | ||

| radicals |

In the mid-1980s—when the question was being decided as to whether any transformation at all would be carried out in our country, and whether these changes would be deep enough to actually “restructure” society—it was the opposition of the conservatives to the progressives that was foremost All proponents of change comprised a united liberal-radical left bloc of sorts, giving little thought to the contradictions among themselves. But from the moment when change became a reality—when the tumultuous process of demolition of old structures began—contradictions among the various interests and values in the progressive camp began to appear and to sharpen rapidly.

The left supported carrying out school reform that would give equal access to quality, diverse and free education. They supported a system of education that would give students free choice while retaining the principle of full equality. They were for various forms of teacher self-management and radical reorganization. Of the entire system of state education. But the liberals’ stake is in cooperative, ultimately private schools for gifted and rich children as well as in the development of elite educational institutions.

The liberal principle is simple: quality services for those who can pay. Appeals to maintaining accessible prices would change little First, prices can be raised, and, second, if the socio-economic reforms proposed around the world by the ideologues of liberalism are implemented, even the elementary maintenance of education, health care and housing will become a luxury.

In our country, Stanislav Feodorov—a talented surgeon who has turned his practice into a brilliantly organized and profitable business—has become the hero of public liberalism. For some time Feodorov’s firm has been offered to society as the model of the new health care system. But amidst the hoopla no one has yet questioned the very fact that joining the quality of medical care to payment indicates an utter abandonment of humanist principles.

But health is neither a privilege nor a commodity to be bought or chosen. From the point of view of the left, it is an individual’s inalienable right. The quality of medical care should not be dependent on the amount of money in one’s pocketbook. While the market allows the possibility of choice among goods, turning health into a commodity means complete indifference to the value of human individuality.

The right to choose a doctor should not be limited by our financial capabilities. The crisis of the old system of social guarantees—which was ineffective, bureaucratized, and allowed a vast amount of room to the mercy of management (“I can give, I can withhold”) and corruption—compels us to struggle for radical reform in this area. But reform may take various directions.

Of course it is simpler to follow the route proposed by the liberals: to create special structures for the chosen, special effective and expensive medicine (or education or housing) for the rich. For the majority everything will be left largely the way it is. In practice, however, such an approach will make everything even worse, since all the quality specialists will be drained into the privileged institutions. Yet the liberal solution is much simpler than creating a system with equal opportunities for all.

The liberal path is safer and more convenient for the traditional apparatus: No one challenges its power. In reality, the liberal circles by no means aspire to break the system of the ruling apparatus. They merely want to create “special zones” for themselves outside this system—and in exactly the same way as “special zones” in the economy will be formed for foreign capital.

Here we see how the interests of “the chosen minority” and the bureaucratic circles coincide. These “radical” measures are crutches for the old system in exactly the same way as mixed enterprises and special economic zones are. They are structures created for maintaining the system’s viability under new conditions, and as a substitute for total democratic transformation.

Only revolutionary reforms advocated by left currents can be an alternative to these liberal reforms. On the whole, the program of the left bloc may be defined in the following way:

1) Market relations are necessary, but they cannot become the chief regulator of social and economic life. The market can play the role of a regulating mechanism, facilitating the responsiveness of the economy, but its action cannot extend to the extra-economic sphere.

2) It is necessary to create an integrated system of self-government and democratic planning—facilitating the access of the masses to the process of making the decisions affecting their lives—as well as a democratic mechanism for the reconciliation of interests. Within the context of democratic planning, a certain kind of market development will inevitably be found.

3) It is necessary to create an integrated mechanism of ensuring social guarantees, of replacing bureaucratic handouts by inalienable and legally guaranteed citizens’ rights. Education, health care and living space must be accessible to all.

4) Political democracy is the highest value: in those cases when interests of some social group or party come in conflict with the interests of democratic development, preference must be given to democracy. If some economic projects do not enjoy the support of the majority, they should not be carried out. This combination of economic and political democracy will create conditions where all the participants of the political struggle and all “interest groups” will be compelled to take into account the interests of other segments. They must seek to develop a strategy that is acceptable to the majority.

5) Where the principle of “the rights of the nation” diverges from “the rights of the individual,” preference must be given to the rights of the individual. The right of the nation to self-determination cannot be realized at the expense of the rights of the minorities and in violation of democratic norms.

The left stands against the conversion of state enterprises into private or stock-based ones. But clearly the current form of state property is incapable of solving the problems facing society. It has nothing in common with socialism. Tzarist Russia had state-owned factories. Even in ancient China and Egypt, the state owned the greater part of the economy.

Democratic transformations are impossible without the conversion of state property into various forms of socialized property. Associations of self-managing enterprises may be created in the place of old ministries, and a significant part of the economy maybe municipalized. Finally, conditions must be created for the emergence of genuine cooperatives—free associations of workers, working through joint means of production and oriented toward the satisfaction of social needs.

The deep reform from below will inescapably lead to the collapse of the old bureaucratic structures. It cannot “work” without free elections, independent trade unions, democratically elected organs of producers’ self-management and workers’ councils at all levels. These democratic structures are vitally necessary in order to facilitate a new decision-making system.

Precisely because of this, the “left model” advances political freedoms for the people to the forefront But such freedoms are not really a necessary precondition for carrying out the “liberal” reform.

It is easy to see that the program of partial liberal reforms within the context of the system is less dangerous for the old bureaucracy. Furthermore, the more radical the market program that is proposed—the more obvious the orientation toward the “advanced experience” of capitalism—the more there is a necessity for a strong hand (and therefore the old apparatus). This is not surprising.

Marx and Engels exaggerated when they said that the ruling ideas of every society are the ideas of the ruling class. Yet itis also indisputable that the privileged layers always—and this includes our own country—possess greater capacity for the development of their political strategy. During the first three years of the Gorbachev reforms liberal circles completely controlled the mass media. They also predominated in the upper levels of official science.

The dominance of liberalism was a necessary stage in the transition from the all-compulsory official dogma to genuine ideological pluralism. In this sense, liberalism has played a positive role in demolishing stereotypes. Initially, too, the left’s ideas were formed precisely within the context of a unified liberal-progressive bloc. Yet as the situation changed, the liberal ideological monopoly has become increasingly dangerous.

It is a painful paradox that the left, having split with the liberals, found the organs of mass media inaccessible at the very time when popular trust in the newspapers and television increased dramatically.

The liberal’s monopoly of the press has led to an enormous devaluation of words. Over the course of centuries in our country, there has been a belief in the mighty power of the WORD. The persecutions that became the fate of the writer, the violence done to Pasternak, Grossman and Solzhenitsyn, people’s heroic struggle to read their works, Bulgakov’s famous “manuscripts do not burn”—all attest to the fact that both the persecutors and the persecuted believed in the power of the WORD.

But now this faith has collapsed. In three years glasnost has erased these preconceptions. Pasternak, Grossman and Solzhenitsyn are being printed—and this does not change anything. Similar to the situation of Western liberalism, repressive tolerance(3) replaced faith in the WORD.

The liberal circles have staked out the official press. At the same time, the left, temporarily forced to the shoulder of the road, has tried to create an alternative press of its own and to work in the mass movements. (For Lenin, it will be recalled, the newspaper is also a “collective organizer.”)

The People’s Fronts, arising in various cities in Russia, became the first manifestation of this tendency toward democratic self-organization. If the political face of the People’s Fronts is not fully defined and the fissure with liberalism is in many cases still ahead, it is because the necessary political experience is still missing. There is also a shortage of competent cadres. Yet all left movements confront such problems in the first phase of development.

Many representatives of the liberal camp perceived a threat in the emerging People’s Fronts. Moscow News has published a series of articles attacking the Moscow NE refusing to allow its members the right of reply. Even greater anxiety was caused in liberal circles by the emergence of the Boris Yeltsin movement In Yeltsin’s speeches there was no clear program, no unified organization. In many cases Yeltsin’s demands resonated with the speeches of the liberals. Nevertheless, Yeltsinism(4) has caused anxiety for the proponents of the liberal project because the masses came out into the streets.

Even before a mass movement emerged in Moscow and other cities under the banner of support for Yeltsin, the newspapers began to speak of “populism.” In the traditional political vocabulary, “populism” means a socially heterogeneous mass movement, having no clear program or established organizational structure, unified by only the most general slogans or by the personality of the leader.

A typical populist movement—despite the predominance of the workers—was Solidarity in Poland. The People’s Fronts are also populist organizations. And the Yeltsin movement is unquestionably yet another populist movement

Liberals rightfully see populism as a threat to their project. Yet when they talk about populism they notice only one aspect of it—its mass character. Actually, not every mass movement is populist. Yet in a country without much political experience, where old social structures are to a significant extent destroyed and new ones are not entirely formed, a mass movement will almost certainly arise as populist.

But in the process of this development, structures of a different type began to form. Organizations more or less capable of carrying out a consistent strategic line began to work out their own ideology and program. In Moscow, for example, such an organization is the Committee of New Socialists. It arose within the People’s Front and quickly managed to become the center of gravity for the supporters of the socialist project, including those outside the MNE.

Populism is the stage of transition for the formation of an organized left movement—in exactly the way that the liberal-progressive bloc was inevitable in the transition from the Brezhnev ideological stagnation to pluralism. The instability of such groupings is obvious. Appeals to the existence of a “common enemy” in the face of the bureaucracy retain supporters of various currents only until it becomes obvious that a significant part of the “progressive bloc” is seeking not so much the opportunity to defeat “the bureaucracy,” but rather accommodation with it As the conservative sentiments increase among the liberals and some populists, the mass of political activists are faced with a choice: turn to the left or to the right.

In the final analysis the program of market Stalinism, in one or another variant, resembles the ideas of the right-liberal and “neo-conservative” politicians of the West and of the Third World. In turn, the ideology of the socialist left in the East corresponds to conceptions of the Western left.

Just as the conditions confronting these politicians are different, the degree of radicalism may also be different But their shared values are apparent It is also not accidental that the Western right applauds the “courageous liberal reforms” in the East, while the left establishes contact with the emerging socialist and self-government movements.

Like ours, Western society is going through a period of changes. And the choice here is analogous: either partial reforms for the chosen—carried out by a strong hand at the expense of the masses—or democracy for all. It is just that in our conditions, with the complete absence of real democratic traditions or institutions, the stakes and risks are much greater Market Stalinism, carried out with all the necessary consistency, can turn out to be many times more cruel than British Thatcherism.

The choice is obvious. Either “perestroika for the elite” will turn into a dictatorship for the masses or revolutionary reforms will lead us to democracy. Our place in the political life of the country will depend on which path we will choose: that to the left or to the right.

Notes

- Cooperatives are businesses organized under terms of Soviet law, prescribing the hiring of labor. They are a transitional form leading toward fuller scale capitalist enterprise.

back to text - People who make their living working in institutions of official Marxism-Leninism.

back to text - This term is a reference to the 1965 essay of Herbert Marcuse, “A Critique of Pure Tolerance.”

back to text - Since this article was written, Yeltsin has been elected Executive President of the Russian Republic, the largest in the USSR.

back to text

July-August 1990, ATC 27