Against the Current, No. 27, July/August 1990

-

A Non-Peace Non-Dividend?

— The Editors -

Black Workers for Justice

— an interview with Nathanette Mayo -

Building from the Grassroots

— Cynthia Bowens -

U.S.C. Out of South Africa

— Harry Brighouse, John Hayes and Michele Milner -

Abortion Pill Is No Panacea

— Joan Batista -

RU 486 Is in the Spotlight

— Joan Batista -

Ford Battles Mexican Workers

— Dianne Feeley -

Soviet Jewish Immigration: Gift or a Time Bomb?

— Michel Warshawski -

The Cancer Epidemic, Part I

— James Morton -

Tracking the Rise of an Epidemic

— James Morton -

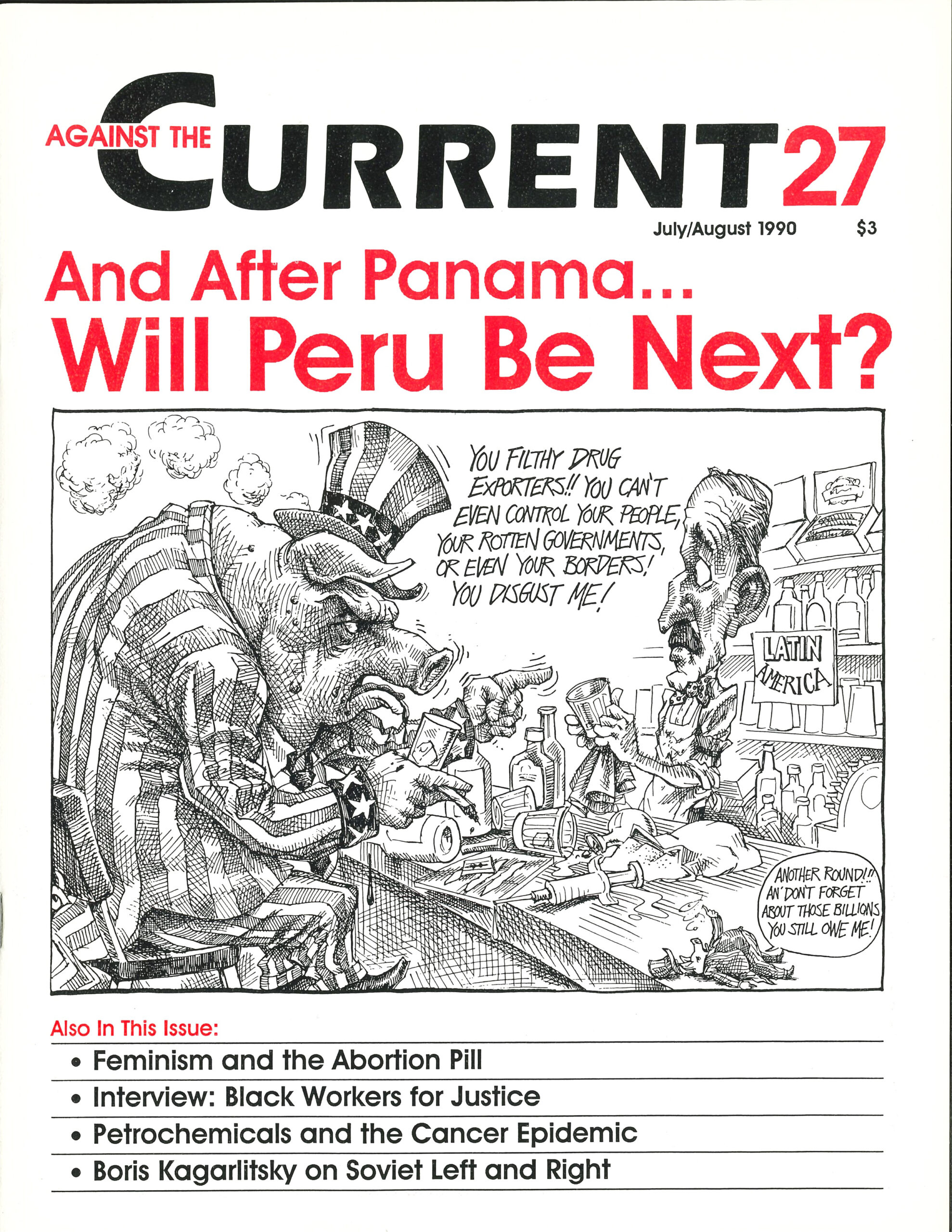

Drug Wars and the Empire

— Peter Drucker -

Mujahideen and Dealers

— Peter Drucker -

The Meaning of the Puerto Rican Plebiscite

— The Taller de Formación Política (TFP) -

Soviet Struggle: What is "Left" and "Right"?

— Boris Kagarlitsky -

Dialogue: The Third World After the Cold War

— James Petras and Mike Fischer -

The Afghans' Tragic Drama

— Val Moghadam -

Afghan: Socialism from Above and Outside

— Samuel Farber -

Random Shots: Summertime Musings

— R.F. Kampfer

Harry Brighouse, John Hayes and Michele Milner

ON FEBRUARY 7, 1990, divestment activists at the University of Southern California met as usual for one of their quarterly protests outside trustees’ meetings. The protest had been organized hurriedly a few days before, when the date of the meeting was made public. It attracted around sixty people, all having reluctantly braved the early morning traffic for the 8:30 am start.

After several speeches, and spurred by the recent announcement of Nelson Mandela’s impending release, the protesters made their way through a building and into an alleyway beside the Board Room. They aimed to be more audible to the trustees, hoping that a delegate could deliver a letter demanding that the trustees publicly pressure the apartheid government to take the reform process further.

In the alleyway, armed security guards and Los Angeles Police Department officers in riot gear met them. A guard struck the first student to leave the building in the face with a nightstick. Within seconds officers attacked the other students.

Protesters entered through the heavy door, resisting violent attempts by officers to push the door shut and crush those in the doorway. One officer hit a woman in the stomach five or six limes. Another slammed a woman against the door and then hit her repeatedly with the full force of a baton.

One officer hit a man across the ear and cheek with his baton; another hit a man repeatedly on the back and then jabbed him with full force in the side. Most of the students report that officers roughly handled and abused them. One officer confronted a student shouting, “Come on, I’m ready for you,” and then began to hit him.

Months of Intimidation

Since the mid-eighties, when U.S.C. failed to divest, divestment has been the rallying cry for the small and beleaguered progressive community at a school with a conservative history.

The administration, unaccustomed to open dissent, has ordered a security presence at divestment events disproportionate to their size. They have had students followed by plain-clothes officers when handing out leaflets, and have threatened to arrest students for standing within 150 yards of the President of U.S.C. James Zumberge.

In this conservative private school, the trustees feel threatened because they know that the protesters, despite their small numbers, have a broad base of support The Student Senate has repeatedly voted for divestment since 1981; the Faculty Senate recently voted for it unanimously.

But still worse—from the trustees’ viewpoint—is that the report of the Committee on Investment and Social Responsibility, appointed by the President in 1986, advised divestment The trustees unanimously rejected the report in June 1989. Since then, divestment protests, although good-natured in character, have been closely monitored by police in riot gear.

U.S.C. is in an unusual situation. In the early 1970s, the administration decided to turn it from a “party” school into a semiserious research university. In pursuit of this goal, they sought two groups of students: foreign students and smart lower-middle and working-class students.

One alumnus objected to these new intellectual aspirations of the university on the grounds that “it is well known that intelligent people are less attractive than others.”

But the consequences of the university’s new look go deeper than that. The Divestment Coalition, for example, is disproportionately populated by this new layer of students, who have very different aspirations from the “traditional” U.S.C. student. A large number are foreign, and although the coalition has only a few Black members, it has cordial relations with the organized Black students, as well as with the large number of AM-can students on the campus.

Furthermore, there is a lot of support from faculty, many of whom are scornful of the administration, and have experience and skills to lend from their own organizing days in the 1960s and 1970s.

And the more traditional students are increasingly responsive to the dissenters in their midst. Within a week of the attack on protesters a letter to the administration, affirming divestment, was doing the rounds at the fraternity/sorority “formal” dinners with considerable success.

Paternalism and Authoritarianism

Accustomed to the apathy of earlier years—when students did little to challenge the authoritarian power structures of the university—the trustees are somewhat embattled.

They have consistently refused to engage in public discussion about divestment, justifying their decision: first, that divestment would have no effect on the situation in South Africa; second, that divestment would hurt the Blacks most, and that we can contribute better to the end of apartheid by working with corporations which treat the Blacks well; and finally, that divestment might be financially irresponsible, by restricting the scope of the investment pool.

The final point is a complete red-herring; no divested institution in California has been approached by the attorney general’s office. The aim of the argument is to suggest that U.S.C. would lose money without actually saying so. They don’t want to say so because it is so clearly false.

The first two arguments, while inconsistent, are essentially paternalistic in content. The idea is that the Trustees and U.S. corporations know better than the people struggling against apartheid—who are calling for sanctions—what is best for them.

Many of the trustees have extensive and well-documented connections with South Africa, and many have visited at the invitation of the government and U.S. corporations doing business there. This, naturally, gives them special knowledge of the situation. Their refusal to make public their personal portfolios fuels suspicions that they have special interests in the corporations doing business there.

However, the trustees’ policy on investment, and the fact that they advance these arguments and refuse to debate or justify them, is a symptom of a deeper structural problem in the university. The problem is the authoritarian and essentially undemocratic manner in which the university is run.

The coalition has repeatedly raised the argument that, being unelected, the trustees have a special responsibility to the university community to carry out their collective will as expressed through representative institutions.

The Rich Know Best

The president, in a subsequent emergency meeting with coalition members, denied this. He explained that the university is a corporation, and thus its trustees must make their decisions independently of any “special interests” expressed on the campus. In other words, he argued that democracy has no place in the workplace, whether that be a factory or a university.

Rather, he thought, rich and unelected people who can be “free of special interest” are best positioned to make policy decisions.

The Divestment Coalition’s meeting with the president revealed further interesting aspects of his philosophy. He told one of the authors that other students “may respect your opinion precisely because you are a white man, and that only the apartheid government was capable of bringing justice to South Africa because the Blacks are too uneducated to do it themselves.

The presidents clarity and breadth of vision is startlingly revealed by the manner in which the meeting came about While the meeting was called ostensibly to ‘restore mutual respect befitting a community of scholars,’ the coalition was summoned at twenty-four hours’ notice by a $375 full-page advertisement The real aim of the meeting, like that of the beatings, was to demoralize the movement.

Both ladies failed. A rally of 250 protested the beatings on February 13. ‘The coalition has filed a civil suit against the school, which has resulted in wide publicity concerning the behavior of security. Most distressingly for the school, which will do almost anything to avoid publicity, the beatings were shown on TV on both the day they occurred and the day the suit was filed.

While the school newspaper—intimidated into submission by the administration—denounced the suit as “selfish,” most students and faculty seem supportive, and individual plaintiffs have even been encouraged in private by middle-level administrators. The caption accompanying a picture in the 1990 school yearbook states that security attacked peaceful student protestors.

Fighting the Power

The coalition has committed itself to initiating a campaign for student, faculty, and staff representation—as well as racial and gender diversity—on the Board of Trustees. It is currently contacting other sympathetic organizations to develop these demands. This fits with the overall perspective of the coalition that support for apartheid does not exist in a vacuum but is a particularly vicious instance of racial and class power relations which they must challenge.

U.S.C. is unusual in that the divestment issue has remained very much alive since the mid-1980s. Most campus movements either achieved commitments from their university administrations to divest or were diffused by the disappearance of South Africa from the news. However, in the coming months there will be renewed activity.

Already, for example, a relatively new anti-apartheid group at neighboring Occidental College has had some success. Four students from Occidental were present at the U.S.0 February 7 rally two spoke at the subsequent protest and are plaintiffs in the law suit.

Meanwhile the Occidental group has drafted a proposal to their own trustees for full and immediate divestment They have held many events on the campus, including a protest for immediate divestment prior to Bishop Tutu’s address on May 16. A crowd of nearly two thousand stood to show their support for divestment, chanting “Divest Now” and “What does Tutu want the best? He wants Oxy to divest.”

Throughout the day students wore red armbands to indicate support for divestment. When Tutu and the new college president arrived, they also wore red armbands. One student said, “We are very hopeful that we are going to win. But we are not complacent.”

On the final day of classes, 200 Occidental students marched to a faculty meeting, where faculty applauded them as they delivered a demand for divestment to the school president.

Many other campuses, including Harvard and M.I.T., have also experienced divestment activity.

The burgeoning struggle in South Africa will be seen on television. Many institutions which committed themselves to divestment in the mid-1980s have failed to divest, abusing the let-out clauses in most divestment measures. Finally, there will be a strong voice from the reactionaries in the world community that the racists in South Africa should be rewarded for recent measures by easing up the financial pressure.

It is precisely now, with the effectiveness of sanctions having been indubitably proven, that pressure must be increased. The friends of apartheid must be resisted. They can be defeated only by mass public activity that challenges the right of corporations to decide what is right for the people of South Africa.

The success of the U.S.0 campaign in keeping the issue alive is due to several factors. The coalition has kept in careful touch with the pulse of the school, and has unstintingly argued for divestment in every forum. They have constantly linked divestment to issues of racism at home: U.S.0 has a dreadful record on Black recruitment, and is on the edge of South Central Los Angeles—a predominantly Black area of the city—making the parallels easy to draw.

They have also worked on other issues: the FMLN offensive occurred during an anti-apartheid week of action, and events were combined; on the anniversary of Roe vs Wade a group of divestment activists staged an impromptu pro-choice rally since none had been organized by anyone else. Thus they have helped to forge a small progressive constituency, while remaining closely attuned to the less active mass of the campus.

Nelson Mandela’s recent insistence that anyone considering the repeal of sanctions either supports apartheid or has no idea what is happening in South Africa reaffirms the need to continue pressuring the apartheid government Students must continue to demand full divestment, combining these efforts with those of students demanding domestic and internal school reforms.

July/August 1990, ATC 27