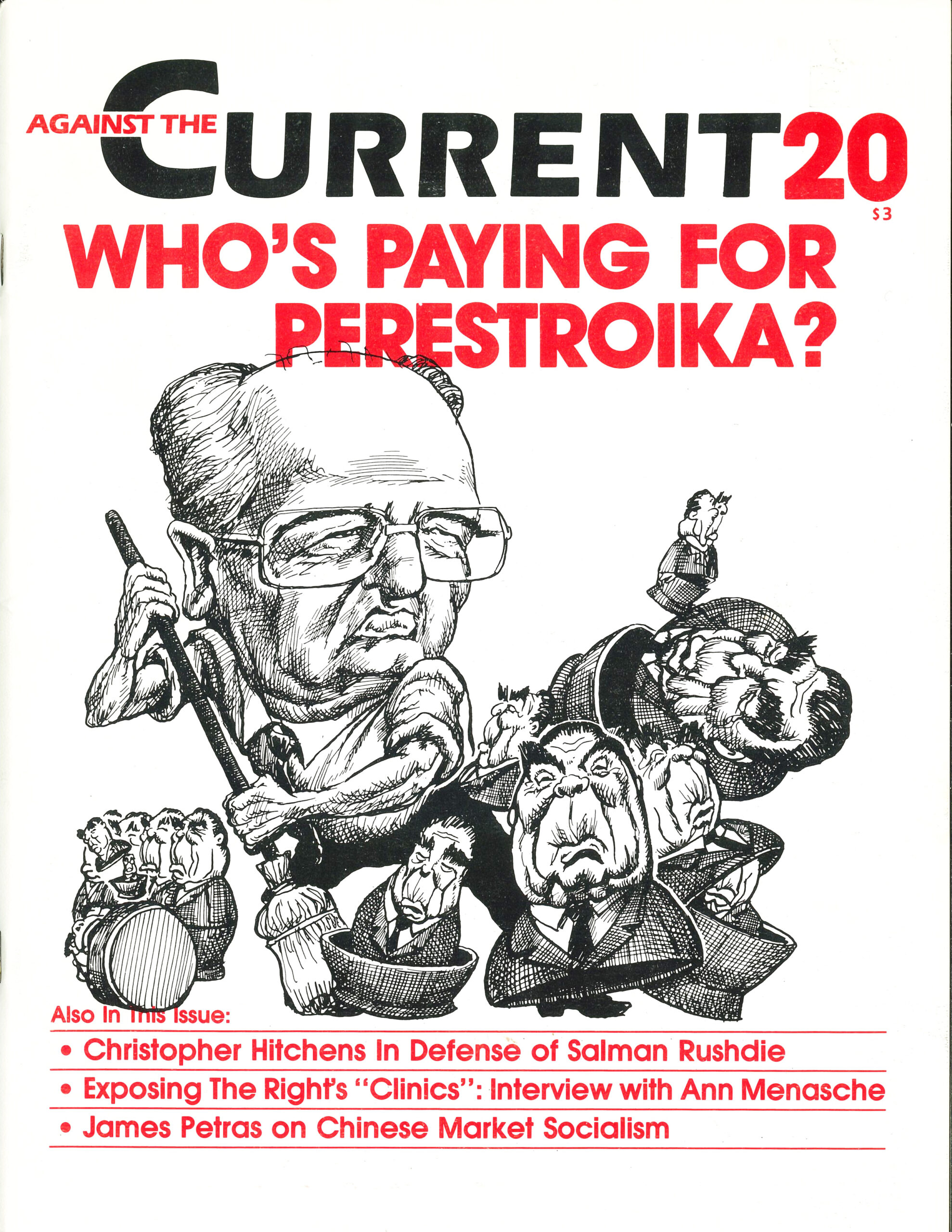

Against the Current, No. 20, May/June 1989

-

Drawing the Line at Eastern

— The Editors -

El Salvador After the Election

— David Finkel -

In Defense of Salman Rushdie

— Christopher Hitchens -

The Right's Phony Abortion Racket

— an interview with Ann Menasche -

The Deadly Health Care Crisis

— Peter Downs -

Contradictions of Market Socialism in China

— James Petras -

Sylvia Pankhurst and the Social Soviets

— Barbara Winslow -

Random Shots: Fat Rulers in Lean Times

— R.F. Kampfer - Viewpoints

-

The Left Press and Puerto Rico

— John Vandermeer -

Child Abuse and the System

— Linda Manning Myatt - Perspectives on Perestroika

-

Conversations in Moscow

— Tom Twiss -

Perestroika and the Working Class

— David Mandel -

Gorbachev: An Appraisal in Human-Rights Terms

— Witold Jedlicki -

Soviet Jewry's Unfinished Agenda

— Larry Magarik - Dialogue on Afghanistan

-

A Further Comment on Afghanistan

— Chris Hobson -

Who's Fighting for What?

— David Finkel -

A Brief Response to Responses

— Val Moghadam - Review

-

1930s Women Writers: A Fresh Look

— Robbie Lieberman

Barbara Winslow

SYLVIA PANKHURST, the socialist-suffragette, is best known today on the left as the person on the receiving end of Lenin’s polemic, Left Wing Communism: An infantile Disorder.(1) Unfortunately little else is known about her ideas and activities as a suffragette who organized working-class women and as a communist feminist who built a revolutionary organization. Pankhurst was and remains today an enigmatic problem for socialists.

Some feminists believe that she was not “feminist” enough, saying that she abandoned her commitment to women’s emancipation in favor of building a communist party. For traditional “Marxist Pankhurst’s heresy began as a suffragette, when she put her energies into women’s concerns, and continued through her now famous debate with Lenin.

Sylvia Pankhurst’s contribution to the socialist, feminist and working-class movements should not be so summarily dismissed. For during the period of international revolutionary upsurge from 1914 to 1924, she was an important figure in the socialist movement in Britain and internationally.

With her conception of the social soviets, Pankhurst made a central, original, albeit neglected contribution to socialist-feminist theory. Social soviets were a means for organizing those often ignored and dismissed sections of the working class and for involving them in the creation of a revolutionary party and in all aspects of the leadership of a socialist revolution. Pankhurst focused especially on working-class women, many of whom were not immediately employed at the point of production.

Socialists today are centrally concerned to link traditional working-class movements with a range of political issues and movements that do not necessarily originate at the workplace, and Pankhurst’s experience of the social soviets is of tremendous interest if we do not want to repeat the mistakes of the past.

Background

Sylvia Pankhurst was a socialist and feminist all her adult life. She muted much of her socialist conviction during the years of militant suffrage agitation, but in 1913 she severed her political relations with her mother Emmeline and sister Christabel. Their disagreements were fundamental. Sylvia wanted the suffragette movement to be a part of the working-class movement for socialism. Her mother and sister wanted a woman’s movement that looked more to the Tories than to working women.

Freer to express herself politically after the break, she focused on building the East London Federation of the Suffragettes (ELFS)-a militant working-class socialist-feminist organization. The ELFS, which Pankhurst founded in 1912, campaigned not solely for votes for women, but the unionization of working women, child care, an end to sweated labor, equal pay, and greater working women’s participation in, and control of, society. The Federation played an important role in the eventual granting of partial women’s suffrage in 1918.

The carnage of the First World War, the bloody Easter Rising of 1916 and the Russian Revolution of 1917 finally transformed Pankhurst from socialist suffragette into a revolutionary. In the struggle to build a revolutionary movement and revolutionary organization in Britain, she was forced to come to grips with a number of political questions: the nature of war, revolution, imperialism, what kind of revolutionary organization is needed in the struggle for socialism, and of course, the relationship between the struggle for women’s emancipation and the struggle for socialism.

The East London Federation of the Suffragettes also underwent tremendous changes. It was renamed the Workers’ Suffrage Federation in 1916, and then in 1918, as part of its commitment to socialist revolution, the Workers’ Socialist Federation. Pankhurst’s newspaper, the Women’s Dreadnought became the Workers’ Dreadnought, reflecting not her lack of interest in working women, but rather her commitment to revolution.

By 1920 Pankhurst was one of England’s most important and, perhaps to the authorities, most dangerous communists. The Workers’ Socialist Federation was a small, but important revolutionary organization. Her newspaper, the Workers’ Dreadnought, was arguably the liveliest, most original and most influential newspaper in Britain at the time. British authorities certainly thought so; they arrested her for printing seditious articles and she served six months in jail.(2)

Pankhurst became an important figure in the international communist movement and in the formation of a British communist party. She had widespread international contacts with leading revolutionaries in Russia (Kollontai), Germany (Zetkin), Holland (Gorter, Pannekoek and Henrietta Roland-Holst), Italy (Gramsci and Bordiga), and even Bela Kun in Hungary. She was a correspondent for the Communist International and for Antonio Gramsci’s newspaper, L’Ordine Nuovo. She travelled to the revolutionary centers of Bologna, Glasgow, Berlin and Amsterdam. In 1920 she smuggled herself into Russia to debate Lenin at a congress of the Third International. Lenin assured Pankhurst international notoriety when he wrote his famous pamphlet, Left Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder, to combat her resolute opposition to the involvement of revolutionaries in any kind of parliamentary activities.

Pankhurst was never as accomplished a Marxist thinker as the other two leading British socialists, James Connolly and John MacLean, but she does fit the description of the “socialist philosopher” offered by Gramsci in his prison notebooks. More important, she was a dedicated, tireless and courageous activist, totally committed to women’s emancipation.

The Soviets

The development of soviets or workers councils has long marked a fundamental point of distinction between revolutionaries seeking socialism from the bottom up-socialism based upon the point of production-and reformists who argue for political representation largely within the confines of the parliamentary model. The appearance of soviets, first in 1905 and then reemerging in the 1917 Russian Revolution, posed new challenges for socialists.

Marx and Engels did not specify in their writings the particular form of working-class organization that would be necessary for a socialist revolution. The Paris Commune of 1871, which gave socialists throughout the world a glimpse of the form and content of a socialist society, did not contain soviets. It was during the 1905 Russian Revolution that the first soviets-or workers’ councils-sprang up. Thereafter Lenin conceived of the soviets as the backbone of any revolutionary workers’ movement and revolutionary strategy. In the months following the 1917 revolution that momentarily brought the Russian soviets to power, smaller workers’ committees were formed in parts of Germany, Italy, Hungary, Methil and Glasgow in Scotland, and Cork in Ireland.

Soviets also emerged during the Hungarian Revolution in 1956, and there were soldiers’ and sailors’ councils during the peak of the revolutionary upsurge in Portugal in 1975. In Chile, cordones or workers’ committees were organized prior to the 1973 coup.

Soviets took the form of workers’ councils inside the factories. In theory they were democratically-controlled with electable, recallable leadership, and they ultimately linked up into a larger representative body. Lenin, Trotsky and other revolutionaries argued that this form of organization was far more democratic because it was based on the Marxist concept that real social and economic power resided at the point of production.

This contrasted with both the bourgeois and social democratic conceptions which held that political power rested in an electorate. Soviets also differed from other rank-and-file organizations, such as workers’ committees, in that soviets contended for power. In other words, soviets posed an immediate and direct threat to the existing political and economic institutions of capitalism.

It was Pankhurst’s long held belief in workers’ control and in a localized, decentralized form of socialism that led her to advocate soviet power. She read more William Morris than Karl Marx and held a somewhat Tolstoyan visionary or utopian view of how a socialist society would be organized. Her view of workers’ power was developed also as a direct involvement in the East End with women’s community and workplace organizations.

In this regard, she drew from a totally different set of experiences than did Lenin, Trotsky or Gramsci. Alone among international socialists, she first built a socialist-feminist organization and only then a revolutionary organization of women and men. During the First World War, the ELFS (later the WSF) advocated and fought for local control of the distribution of food, of welfare and relief agencies and of children’s centers. Pankhurst even organized a cooperative toy factory, maintained under what she believed to be workers’ control.

The Russian Revolution and the reemergence of soviets changed Pankhurst’s conception of socialism and revolutionary organization. Her espousal of soviet power came from her disillusionment and impatience with parliamentary forms of democracy. She believed bourgeois parliaments could no longer solve the problems of war, poverty and women’s oppression. She was quite explicit about why soviets were superior to other forms of government, the unrepresentative and undemocratic nature of bourgeois democracy:

“As a representative body an organization such as the All-Russian Workers’, Soldiers’, Sailors’ and Peasants’ Council is more closely in touch and more directly represents its constituents than the Constituent Assembly or any existing Parliament. The dele gates … are constantly reporting back and getting instructions from their constituents; whilse Members of Parliament are elected for a term of years and only receive anything approaching instructions at election times. Even then it is the candidate who, in the main, sets forth the programme, the electors merely assenting to or dissenting from the program as a whole.”(3)

The soviets, she believed, had an advantage over other forms of democracy in that by being organized along occupational lines they would reflect the organization of the working class itself. Pankhurst explained in an article in the Dreadnought that the soviets did, in fact, solely represent the working class. This was precisely the Bolsheviks’ vision, and something that all socialists should support, since under socialism, “everyone will be a worker and there will be no class save the working class to consider or represent.”(4)

After 1918 soviets became more central to Pankhurst’s politics. They are, she said, “the most democratic form of government yet established.”(5) Accounts of how soviets worker, or were supposed to work, appeared frequently in the pages of the Dreadnought. Pankhurst made a six-month tour through revolutionary Europe in 1919, stopping in Bologna, Italy expressly to observe a soviet in action.(6) The next year she visited Russia, not only to participate in the Congress of the Third International, but also to see firsthand, Russian soviets.

Soviets and soviet power have been a crucial organizational form of revolutionary workers’ power. Yet surprisingly little is known about the Russian soviets and how they operated. We know even less about the role of women in the soviets. There were large textile and munitions factories in St. Petersburg and Moscow, employing thousands of women: were there all-women’s soviets? Were women in leadership positions in soviets? Did women’s soviets or soviets with a majority of women issue different demands or programs? Did any political party fare better with men than women? Did women involved in soviet organization attempt to reach Russian housewives? Were “women’s issues” taken up in the soviets?

What Pankhurst attempted to do in very different circumstances was to raise these questions and find practical answers. She wanted to apply the principles of the Bolshevik revolution to British conditions.

The Social Soviets

Pankhurst first raised the idea of social soviets in 1917 at a labor and trade union conference in Leeds. The conference resulted from the tremendous wave of enthusiasm toward the Russian Revolution that engulfed the British working class.(7) It seemed, for a brief period, that Labour Party leaders and trade union officials might even attempt to take a major part in the formation of an alternative revolutionary government in Britain.

The conference proposed that Councils of Workmen’s and Soldiers’ delegates be set up on the Russian model. Pankhurst was an active and aggressive participant. The WSF demanded that the “Councils of Workmen’s and Soldiers’ Delegates” be changed to read the non-gender-specific “Councils of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Delegates.” Like today’s socialist-feminists, WSF members knew that words and titles reflect a reality. In fact the Dreadnought claimed that the word “workmen’s” was a mistranslation from the Russian original.(8)

Pankhurst won the argument and further demanded that women be an integral part of the organization. The WSF insisted that the local organizations formed after the conference be called the Workers,’ Soldiers’ and Housewives’ Councils. Again Pankhurst argued that unemployed women and housewives were also working class and therefore must be included in any and all organizations that claimed to be socialist.

And yet she was skeptical about the future of the organization. She was nominated to serve on the executive committee, but declined because she did not feel that the promoters of the movement were serious. She was also contemptuous of the tokenism that provoked her nomination. In an observation that sounds all too familiar to women today, she acidly pointed out that “they cast their eyes round for a woman. One woman was enough to put on a committee these days, but one woman they must have to placate the suffragists.”(9) Despite her refusal she was elected by a large majority as the sole representative for London and the Southern counties.(10) Her pessimistic appraisal of the conference was well founded; the organization collapsed after its third meeting.

Nonetheless, debates about the nature and the creation of soviets continued in England and elsewhere. As Pankhurst wrote about Italian and Russian soviets in the Dreadnought, the leading Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci was raising questions about the nature of soviets and workplace organization. However Gramsci omitted any mention of housewives.(11)

In early 1919 the Socialist Labour Party of Britain (SLP) published its “Plea for the Reconsideration of Socialist Tactics and Organization.” They advocated the adoption of traditional ideas of industrial unionism, and discussed the relationship of unionism to their political party, their own experiences in the workshops, and the developing revolutionary situation. The article pointed the way toward anew society based on soviets. In the same vein was William Gallacher’s pamphlet, Direct Action. In The Workers’ Committee: An Outline of the Principle and Structure, J.I. Murphy also provided a farsighted account and assessment of workers’ committees. But consistently missing from all of this ferment about socialism and soviets was any discussion of the role of women.

The exact nature of soviets and their relationship to a revolutionary party-at least in the traditional Leninist sense-was not very clear to Pankhurst, Gallacher, Murphy or most other British revolutionaries. Lenin argued that British revolutionaries confused soviets with the party. Pankhurst, like other British revolutionaries, believed soviets were simply workers’ committees and also synonymous with local branches of a revolutionary party.

In January 1920, the National Action Committee (NAC), an organization representing many of the militant and revolutionary workers’ organizations in Britain, decided to call a rank-and-file convention to be held in London. All the shop stewards and workers’ committees in the country were invited. Pankhurst was delegated to draw up the agenda or the conference that was to discuss theories of soviet power. It was at this conference that Pankhurst proposed and pressed her ideas of the social soviets.

A small group of fourteen people was appointed from the rank-and-file convention to form soviets throughout Britain. They were charged with setting up committees for propaganda purposes and call them district soviets. They were to compile lists of food supplies and machinery in order to be prepared for the revolution they believed to be so near.(12)

There was another reason, along with the desire to emulate Russian soviets, for the rank-and-file convention’s adoption of the idea Of social soviets. By 1920, the power base of the shop stewards’ movement, the backbone of the revolutionary working-class struggle in Britain, had been whittled away and was in retreat. The movement was searching for an identity and seeking support outside the immediate confines of the engineering and munitions factories. Revolutionaries were looking for a way to save and revitalize what remained of the movement.

Social soviets or social committees, based on organizing workers where they lived, rather than where they worked, provided a possible answer. Unemployed engineers (machinists) could be brought back into the mainstream of the movement, since belonging to a social committee or social soviet would not depend upon being employed in a particular workshop.

Following the convention, Pankhurst and the WSF embarked upon an intensive campaign for the formation of social soviets.(13) Joe Thurgood, a member of the WSF from Kent, became the organizer of the social soviets. He was a bootmaker, a keen supporter of the Bolsheviks with considerable influence among postal and railway workers.

Thurgood outlined in the Dreadnought that there would be two types of soviets – industrial and social. The workers’ committees would be based upon workplace or factory organization; this would be Thurgood’s area of work. Pankhurst was to organize revolutionaries socially — where they lived. These soviets would then be transformed into branches of a communist party as it developed.

Pankhurst believed that soviets already existed in Scotland in the form of social committees. She urged that the Scottish example be followed throughout the country. In London, Pankhurst hoped to organize a group of sympathetic comrades to canvass local trade union and socialist organizations on the issue.

Feminism and Soviets

Pankhurst attempted to relate Lenin’s and Trotsky’s analysis of soviets with her vision of feminism:

“These are the workshop committees of the mothers for the streets and the houses where they live and work are their workshops. The women must organize themselves and their families and to help in the general struggle of the working class conquer the power of government.(14)

She added that the social soviets were necessary “so that mothers and those who are organizers of family life of the community may be adequately represented and may take their due part in the management of society.”(15)

Here, then, was the crux of Pankhurst’s revolutionary feminist politics. The majority of women in the East End, her immediate constituency, were not employed in large factories. They were housewives, quite often married to dockworkers, gas workers or other laborers.

Those who did work were employed in either small firms of three to five workers, or earned their living as homeworkers or domestics. These were the women who had demonstrated and rallied for the vote in 1913, had organized to defend the East End community from the ravages of war time, and now were involved in the revolutionary upsurge.

These women were not, in the traditional Marxist and Leninist sense that section of the working class central to production of surplus value and therefore central to the creation of a revolutionary party. But these women were working class, were fighters, and their concerns about control of family and community life were as valid as the concerns about workers’ control of the factories. Pankhurst wanted to utilize the energy, talent and fighting capacity of these women. She attempted to forge a revolutionary organizational form specifically suited to the lives of the women she knew.

Furthermore, those workers in the “strategic” industries did not raise women’s and family issues. For Pankhurst, social soviets were the only way in which women’s demands would be an integral part of a revolutionary movement.

In March 1920 Pankhurst spoke about soviets at the Bow Baths, a local meeting place. Her speech was reported in the outraged East London Advertiser. At the meeting, the hall was decorated with huge WSF banners proclaiming ”Welcome to the Sovietsl” Pankhurst praised the German and Italian soviets, claiming they were gaining ground. She argued that the continual rise in food prices would make women rebel. She urged that “we have got to have soviets in our streets, in our workshops and in our factories.”(16)

At the same meeting, Harry Pollitt, a leading working-class militant, WSF member and later founding member of the Communist Party, told the women of East London that raiding the docks would be one sure way of bringing down prices. Melvina Walker, who chaired the meeting, called upon everyone to follow the example set by Russia.

In late March the Dreadnought published Pankhurst’s “Constitution for British Soviets.” Street organization, she argued, was the key to the organization of women into soviets. She pointed to the block associations East End women organized. They held elaborate children’s parties celebrating peace. These involved concerts and pageants. Pankhurst saw these as proof of the warner{s capacity to work together cooperatively and make democratic decisions.

But most important, Pankhurst argued, women had to organize soviets to protect themselves and their families from rising rents and food prices. The Food Controller and the Ministry of Food would not do anything to help working-class families. The Labour Party, through the local councils, had failed to keep food prices down. The only remedy was to place land, industry, food supplies, milk, trams, buses and houses in the hands of workers’ committees or soviets. As always, Pankhurst’s appeal was made through the problems that were of direct interest to women.

Her constitution emphasized “household” soviets. Her whole argument and frame of reference centered on involving women in the revolutionary process. Her plan was quite precise:

“The population of Poplar at the 1911 census was 162,449 and these were 35,179 families or separate occupiers. Each of these would mean a member of the Household Soviet. Fifty members of the Household soviet would make 701 Soviet areas. The Poplar District Household soviet would therefore subsist of 701 members. As the number is rather large, Subdistrict Household soviets could be formed in Bow, Bromley and Poplar.”(17)

This would then become the basis for town soviets, regional household soviets, household soviets in rural areas, county rural household soviets, industrial, public health, educational, army and agricultural soviets.

Pankhurst’s vision was important. She was acutely aware of the lack of industrial power women had, and hence their relative lack of social power. Her vision of the soviets was a production of her long held belief in the local organization of a socialist society, her practical experience in working with the women of the East End and her understanding of soviets in Italy and Russia.

Pankhurst’s conception of social soviets poses serious questions for Marxist feminists in a number of areas. Pankhurst had not intellectually grappled with the sexual division of labor.

The basis for Pankhurst’s formulation of social soviets was that women’s work was located in the home and community. She acknowledged that while provisions had to be made for individual men who did not have housekeepers, the household soviet was for women.

Men worked in factories, and therefore would be represented in the industrial soviets. She also believed that women who worked outside the home for pay would be adequately represented by the workshop or industrial soviet. Would women in the paid labor force enjoy double representation in both the industrial soviet and the household soviet, for example? But Pankhurst really never looked at the complex issue of women’s double role at home and in the workplace.

A second, and equally pressing issue touched upon by Pankhurst, was that of the potential economic and social power of housewives organized in the community. Pankhurst’s initial discussion of the social soviets anticipated the theoretical questions of the exploitation of, and production of surplus value, by women working in the home. The issues of housework and the role of non-employed working women is one of great concern to Marxists and feminists today. Pankhurst wrote and agitated around the issue of women’s housework — but not from the point of view of challenging the sexual division of labor. Her political activity and commitment was dedicated to revolutionizing the home, community and work situations of women in the East End. She was particularly concerned with the health and welfare of mothers and children.

From 1918 to 1924, the Dreadnought carried articles about women and socialism, ranging from the need for communal laundries, restaurants, and clothes mending shops. Such places would be staffed by professional houseworkers (the implication being that the majority of these professional homeworkers would be women and the children cared for by the state.(18)

Again, these ideas reflect Pankhurst’s acceptance-perhaps tacit, perhaps grudging-that there was men’s work, the factory, and women’s work, home and family. She does not ever acknowledge the possibility that women and men might share housework and childrearing, although she envisions technology doing away with most household tasks.

Ina sense Sylvia Pankhurst was a pioneer trapped inside some of the cultural assumptions of her time. But whatever her inability to come to grips with the issue of the gender division of labor, it must be remembered that this issue was not addressed by either Marxists or feminists at the time. Pankhurst could not stand on the shoulders of others who had written and agitated on the subject. Like Alexandra Kollontai, the Russian revolutionary feminist, Pankhurst was starting out alone.

A Socialist-Feminist Forerunner

In spite of Pankhurst’s determination to build soviets, neither she nor the WSF were able to organize such formations either in the East End or in other areas, Pankhurst, like most of her contemporary British revolutionaries, was wrong in her assessment of the possibility of revolution in Britain.

She also was unclear as to the outward nature of soviets and how they developed in Russia, Germany and Italy. They were formed during a period of revolutionary working-class upheaval, not one of working-class retreat, which was slowly happening in Britain.

Furthermore, working-class organizations, such as the ones that organized the peace campaigns in the East End, or the workers’ committees in Scotland, were not soviets. Soviets were workers’ organizations that contended for power. Revolutionaries cannot build soviets by either passing resolutions for their existence or wishing for their formation. Even Sylvia Pankhurst’s inexhaustible will and determination could not build soviets out of a working class in retreat.

The concept of social soviets was important, even if at the time unrealizable. Pankhurst was trying to reconcile her wish to organize working-class power with her knowledge and direct experience that those members of the working class who were not skilled, male factory workers must be represented and active participants in their own revolution.

For all the problems discussed, it must be added that Pankhurst did focus on a problem that other socialists ignored and omitted: How can women be drawn into the revolutionary process? In this respect, Sylvia Pankhurst can be considered a foremother of today’s socialist-ferninists. Our understanding of the relationship between socialism, feminism, the working class, soviet power and revolution would be far richer had more marxists and feminists been involved in the debates and discussion of the social soviets.

Notes

- This article will not take up the subject of whether or not Pankhurst lived up to her reputation as an “infantile leftist” That subject is included in a book I am writing on Sylvia Pankhurst: Socialist Suffragette and Communist Feminist.

back to text - The article that was responsible for Pankhurst’s arrest was written by Claude McKay, the Jamaican revolutionary who was writing for the Workers’ Dreadnought McKay was exposing racism in the British armed forces. Pankhurst was also unique among British revolutionaries in that she was an active anti-racist.

back to text - Workers’ Dreadnought, Jan. 26, 1918.

back to text - Ibid.

back to text - Workers’ Dreadnought, June 9, 1918.

back to text - Pankhurst’s description of her journey to Europe is found in her unpublished autobiography called The Red Twilight which is at the International Institute of Social History Amsterdam (IISH).

back to text - Walter Kendall, The Revolutionary Movement in Britain, London Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1969, 174-6; What Happened at Leeds: A Report of the Leeds Convention of 3 June,1917,edited by Ken Coates for the Archives of Trade Union History and Theory Series #4, n.d. It was originally published by Pelican Press.

back to text - Workers’ Dreadnought, July 21, 1918.

back to text - Sylvia Pankhurst, “When I Sat with the Present Prime Minister on the Executive of the Council of Workers and Soldiers,” unpublished article, 1931, IISH, 214.

back to text - Fawcett Library, Autograph collection, Vol. XX, Part 1.

back to text - Antonio Gramsci, Selection from the Political Writings,1910-1920, editor Quenton Hoare, London, Lawrence and Wishart, 1977, 66-7.

back to text - Evidence for this comes from three sources: The Pankhurst Papers in Amsterdam, the Workers’ Dreadnought in March 1920 and Home Office Intelligence Report CAB/24 CP 960, March 25, 1920.

back to text - Workers’ Dreadnought, March 27,1920.

back to text - Ibid.

back to text - Ibid.

back to text - East London Advertiser, “Bolshevik Poison in Bow Baths,” March 20, 1920.

back to text - Workers’ Dreadnought, March 27, 1920.

back to text - Ibid.

back to text

May-June 1989, ATC 20