Against the Current No. 19, March/April 1989

-

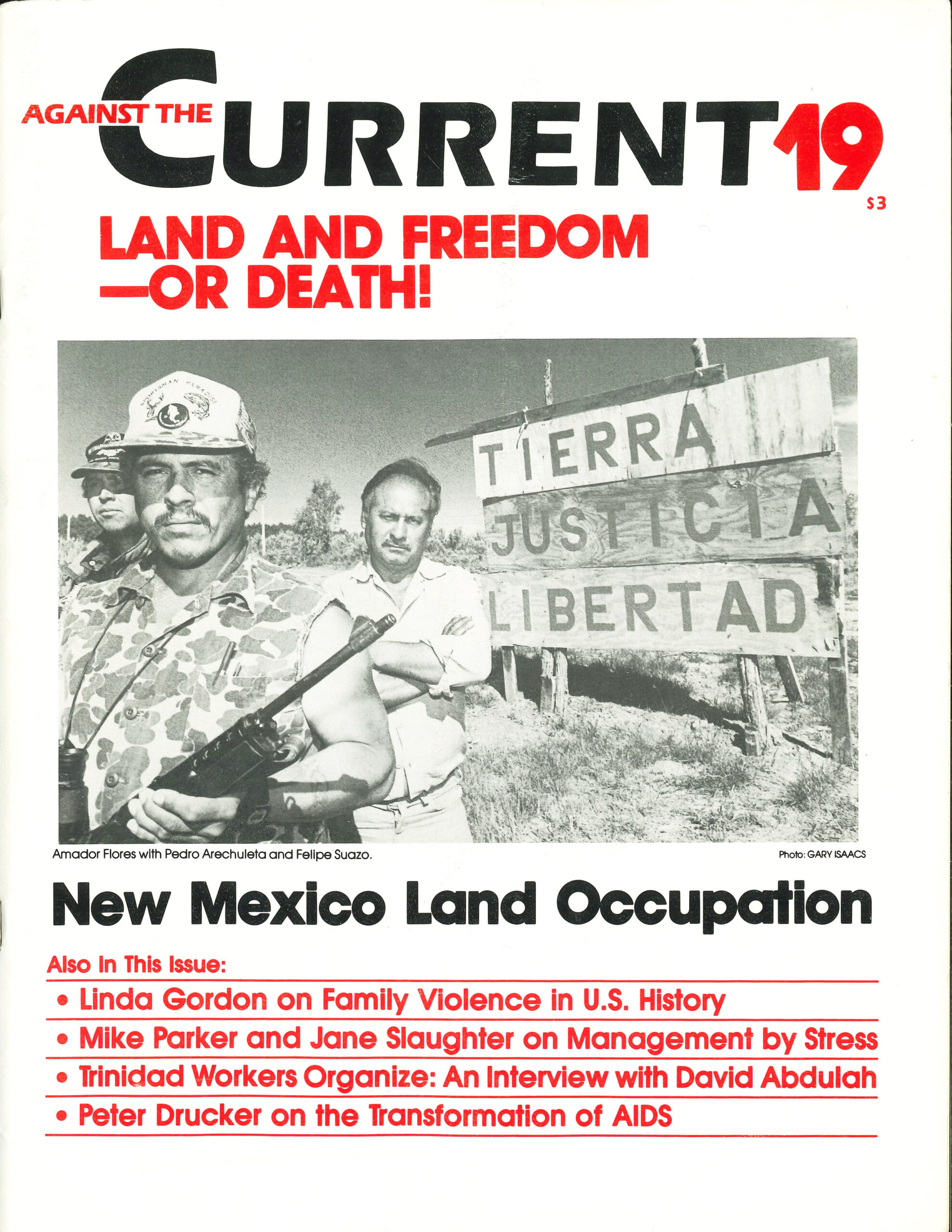

Struggling vs. Theft of Communal Lands in New Mexico

— Alan Wald - Mexican Activist "Disappeared"

-

Defending the Right to Choose

— Norine Gutekanst -

The Transformation of AIDS: Polarization of a Movement

— Peter Drucker -

The Politics of Child Sex Abuse

— Linda Gordon -

Random Shots: Wisdom of Solomon

— R.S. Kampfer - Capital Restructures, Labor Struggles

-

Free Trade . . . for Big Business

— Francois Moreau -

Management's "Ideal" Concept

— Mike Parker and Jane Slaughter -

Other Points of View

— Mike Parker and Jane Slaughter -

U.S. Labor & Foreign Competition

— Milton Fisk -

Review: Class Struggles in Japan Since 1945

— James Rytting -

Trinidad: Toward a Party of the Workers

— David Finkel & Joanna Misnik interview David Abdulah -

A Brief Glossary of Abbreviations for Caribbean Parties

— David Finkel - Dialogue

-

Reclaiming Our Traditions

— Tim Wohlforth -

A Comment on Afghanistan

— David Finkel -

Socialism from Below, Not the PDPA

— Dan La Botz -

Islam, Feminism and the Left

— Christy Brown -

A Brief Rejoinder

— R.F. Kampfer - In Memoriam

-

In Honor of Max Geldman

— Leslie Evans

David Finkel & Joanna Misnik interview David Abdulah

David Abdulah is treasurer of the Oil Fields Workers Trade Union in Trinidad and Tobago and has served on the union’s national executive since 1982. He has been employed by the union for eleven years as an education and research officer.

He is also the convener of the Committee for Labour Solidarity (CLS), a political group that describes itself as “a collective of trade unionists, political and community activists whose basic commitment is to build the solidarity of the working people as a class, which is the pre-condition for the working people to carry out their historical mission to transform the existing economic and political system into a new order.”

The CLS has been carrying out extensive grassroots organizing toward the foundation of a new mass party of the Trinidad and Tobago working class. As David Abdulah explains in the accompanying interview, the Trinidadian workers’ movement is of pivotal weight in the class struggle in the Caribbean.

The development of a mass workers’ party in Trinidad should not be viewed in isolation. It is part of a broader process that in recent years has seen the emergence of the Workers Party (PT) in Brazil and the rise of massive militant trade-union organizations in South Africa, the Philippines and South Korea — organizations fighting for genuine unionism and working in opposition to pro government U.S.-based labor bodies.

The importance that the CLS has placed on rank-and-file power and the creation of structures that will be energized and control — led from below means that a new party will be based on solid foundations, not simply on programmatic proclamations and good intentions. It is a process that North American socialist activists may find most educational as well as encouraging.

David Abdulah visited Detroit in November 1988. This interview was conducted for Against the Current by David Finkel and Joanna Misnik.

David Abdulah: To begin with a quick history, the Oil Fields Workers Trade Union is fifty-nine years old. From 1962 to the present, it has been thoroughly democratic.

In June 1937 there was an anticolonial revolt, with workers of the entire area arising against [British] colonialism and the conditions arising from it Within days after the revolt was violently crushed by British marines, workers in oil and other industries began to form organizations to defend their interests — hence the formation of the Oil Fields union.

The union always had an outlook that we weren’t only out for a five- or ten percent increase, but to advance the interests of all workers in Trinidad and Tobago. Every local officer is elected by direct secret ballot annually, and the shop stewards every two yean. We have also maintained independence; we’re not run by any political party as is common throughout the Caribbean. This democracy and independence are the roots of the union’s strength.

The Committee for Labour Solidarity

(CLS) was formed in 1981 as a collective of political, cultural and community activists — a preparatory political organization. We have worked for labor solidarity across lines of unions, jobs, etc., to develop the consciousness of the working people in all their struggles and to lay the groundwork for a new political party.

On November 12, 1988, we had a massive assembly of 1,200 people, which mandated the CLS to organize the founding of a new party for April 1989.

ATC: You come from a struggle for democratic trade unionism — how would that culture be brought into the party?

D.A.: This is an important point. Obviously our outlook has been changed by the work in the trade-union movement. For example, in the CLS and certainly within the party, there is and will be a great deal of democracy. We have not finalized the structure, but we recognize that the strength of the working class is predicated on the active involvement of the members in determining where the movement goes.

The strength of the Oil Fields Trade Union itself is based on the strength of the rank and file. For example, my colleagues and I go frequently to the shop floor to talk directly with the workers, quite apart from the local branch meetings, which not everyone attends. We are in constant contact through what we call COSSABO, the Conference of Shop Stewards and Branch Officers. This body first arose in the Oil Fields union in the 1970 strike, to free prisoners and resist some proposed fascist legislation [that would have placed extreme restrictions on union activity –ed.]. It has remained ever since as an instrument of workers’ mobilization and popular democracy.

We had enough leaders to form a party in 1981, but that would have been fundamentally elitist We formed, instead, a preparatory organization We could have formed a party last Saturday at our convocation-that also would have been elitist and undemocratic. The activists have to go back to the base and discuss the proposed platform.

So we aren’t simply asking people to vote. For example, our position always was that the party will be formed when the people are calling for it, not before. In the past year people have been saying to us, “we want a workers’ party.” We talk of two components — institutions of worker and popular power and a new kind of political party. These must go hand in hand.

ATC: What is the total size of the population and the working class? And what is the base of the CLS?

D.A.: The population of Trinidad and Tobago is l.2million. The official size of the labor force is 470,000. We have a very young population, and the labor force statistic doesn’t include discouraged workers, housewives or unemployed youth … and there is 23% official unemployment. So you’re talking about 350,000 employed. Of that, just 100,000 are organized.

The leaders of the CLS are the leaders of the progressive unions — the sugarcane farmers, food co-op farmers, communications workers, oil workers — and we also have key people in the teachers’ movement. In the progressive union movement [the Council of Progressive Trade Unions] we have about 35% of the organized workers. The Trinidad and Tobago Council, backed by AIFLD [the American Institute for Free Labor Development, run by the AFL-CIO and the U.S. State Department] has more, because their federation has the government workers and public servants. Our movement dominates in all the key industries and among farmers.

There are two large unions not belonging to either federation: the teachers with 10,000 members and the sugar workers with 6,000-7,000.

ATC: What specific impact does the general crisis of the less developed countries - debt, for example — have on your own economy and working class?

D.A.: There is a massive economic, political and social crisis in the country. Oil contributes 90% of our foreign exchange, so when the price of oil fell and the international energy economy began to reorganize, our oil industry became redundant. We had a drastic fall in production, price and refining-from 1981 to 1983 our foreign exchange earnings were cut virtually in half.

Unemployment went from 10% in 1981 to 20% in 1985 and 23% today — a loss of 70,000 jobs with a rapid increase in crime, family breakdowns and violence, substance abuse, and a return of pauperization that many Trinidadians never thought they would see again. Real wages have fallen by 25% in the past four years. There are families with both parents unemployed for several years, unable to send their kids to school. Now if, let’s say, Dominica [a small Caribbean island state] has high unemployment, since it’s a rural society people can at least feed themselves. Trinidad is an urban society and so the level of desperation is higher.

The crisis is massive and getting worse, because the government is intent on negotiating an agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). I have quoted extensively in a speech I gave to Parliament from the letter of resignation by the senior IMF economist, Mr. Davison Budhoo of Grenada, who worked for the IMF for eleven years. He gave a full account of IMF wrongdoing: statistical fraud, manipulations to force devaluations, sabotage of a country’s institutions and the measures imposed for any loan The government is already moving to privatize [state] industry, and to cut its wage bill by early retirement of thousands of government employees.

The political crisis exists because of: a) the economic and social crises, exacerbated by b) the split in the present ruling party, the National Alliance for Reconstruction (NAR). We have to explain some political history here.

From 1956 through 1986 there was one party in government, the Peoples National Movement (PNM) of Eric Williams. This was a nationalist party led by middle-class professionals, who make nationalist analyses but are totally incapable of confronting the essence of the problem, the local and foreign elite.

There was a strong Caribbean radical movement in the early ’50s-with Cheddi Jagan in Guyana, the left wing of the Peoples National Party (PNP) in Jamaica, etc. In 1944 the Caribbean Labor Congress (CLC) was formed by all the labor-based political parties and trade unions in the region. They called for in dependence and an all-Caribbean federation (not just the English-speaking countries).

The British and U.S. set out to systematically break up this movement. Cheddi Jagan won an election, so they brought in troops, imprisoned the whole government, brought in Forbes Burnham, split the Peoples Progressive Party (PPP-Jagan’s party) along racial lines, and the like. In Jamaica the left wing of the PNP was expelled. The Trades Union Congress was destroyed and the right wing of the PNP set up its own National Workers Union, which received assistance from the U.S. unions.

Then they broke up the CLC by forming a Caribbean Division of ORIT [the U.S.-backed labor federation for Latin America]. Thus the possibility of mobilizing the Caribbean workers through the CLC was destroyed by the [pro-West] International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) and later AIFLD.

Neocolonialism and Resistance

In Trinidad the British cultivated Eric Williams’ PNM with its middle-class leadership to ensure that it would set up a nice neocolonial regime. They agreed to a federal government without independence — a parliament and a prime minister without power. So when independence was finally granted [in1962], it was guaranteed that a neocolonial policy would be followed, that there would be no tampering with economic relationships.

In 1970 there was a serious popular attempt to remove the PNM, with mass demonstrations, a two-month-long insurrectionary movement and an army mutiny. This was only staved off with the intervention of U.S., Venezuelan and other foreign troops as well as police action and a state of emergency. The people wanted to make a fundamental break.

That protest movement continued after 1970 despite the state of emergency in effect in 1971-72. There were strike movements in oil and sugar in 1974 and ’75. The crisis didn’t reach another high point for only one reason, the oil boom from 1974-81. The PNM survived because of the petrodollars. In 1973, with only six weeks of foreign exchange in the treasury, Eric Williams announced his retirement at his PNM’s party conference — but before the party could choose a new leader there came the Israeli-Arab war, the price of oil skyrocketed and Williams came back.

With the decline of oil prices from 1982, the PNM’s popularity collapsed. The popular struggle resumed and culminated with the PNM’s removal in 1986 and the election of the NAR (National Alliance for Reconstruction). The NAR was a coalition of three main parties: the Democratic Action Congress (DAC) based in Tobago, which is the party of the present Prime Minister Robinson; the Organization of National Reconstruction (ONR) of Carl HudsonPhillips, who like Robinson is a former PNM cabinet minister-in fact, he’s a right-wing former attorney general close to the Jamaica Labor Party and prosecutor in the Coard trial in Grenada; and Basdeo Panday’s United Labor Front (ULF), which was originally fanned out of the strike movements of 1974-75 by sugar and oil workers and farmers.

ULF was born as a trade-union grouping at the height of this strike wave. Later the workers discussed their experiences, decided to intervene politically and to make ULF a political party in 1976. We won ten parliamentary seats and became the official opposition.

ULF however split in 1977 between the Panday faction and the faction led by Raffique Shah, the president of the Cane Farmers Union, who had been a central figure in the 1970 army mutiny. After he got out of jail the farmers invited him to organize a democratic union. The Panday faction had the majority support, because as leader of the sugar workers he was the traditional leader of the East Indian community in the country — that is the legacy of the British success in keeping workers divided by race. Also, Panday is Hindu while Shah is Muslim. [Editors’ note: The traditional racial division in Trinidad pits East Indians against Blacks. Historically, East Indians were brought to Trinidad as indentured labor following the abolition of Black slavery. The Committee for Labor Solidarity argues that the middle-class forces among both East Indian and Black communities have a vested interest in preserving this conflict, while the unity of the Indian and Blackworkers can “lead this country not only out of the racial conflict but … into economic prosperity” (Raffique Shah, Race Relations in Trinidad: Same Aspects, CLS pamphlet, 1988).]

Our faction [Shah] was the radical wing, Panday’s ULF, generally representing the professional middle classes, therefore went into the electoral alliance with DAC and ONR to form the NAR that won the election massively in 1986. The former ruling party PNM went from twenty-six seats down to three in the thirty-six-member Parliament.

But Robinson and company failed to capitalize on that historic moment. Having no faith in the people, they did everything to alienate the people, bringing in anti-labor measures. Within six months ministries were openly condemning each other; within a year there was a cabinet shuffle and shortly after that Panday was fired from the government.

In November 1988, less than two years after the election, the coalition partners have irretrievably split. Panday has fanned a new party called Club ’88, which had a mass rally three weeks ago of 20,000 people. That has made the political crisis worse. You have a totally unpopular prime minister, a ruling party completely split, all its promises in collapse — and reports in the press speak of very low morale and rank-and-file protests in the army.

There is a great deal of drug traffic from Venezuela, overcrowded prisons and all the indicators of an immense crisis. Another 1970 is on the agenda; the situation that was suspended after the popular uprising then has returned, with a vengeance.

ATC: Your Committee for Labor Solidarity seems to come out of the split you mentioned in the ULF, right? Where does CLS see itself in relation to this unfolding situation?

D.A.: Right, the CLS used to be the Shah faction of the ULF. We were the radical wing of that movement. We’ve all come from different backgrounds and experiences — Shah came from his experiences in the army, for example. We don’t have a “leader.” Raffique hasn’t been identified as a leader as much as in earlier years, even though he’s very much a member and was one of the speakers at the convocation of 1,200 people I mentioned before. As for my own background, I was a campus activist from1972-74, then with ULF and then with the labor movement.

There are now no women on the steering committee of the CLS; this is a historical thing given where we came from. But there are women activists. When we become a party, the leadership will change to reflect our society.

ATC: Will there be two parties — yours and Panday’s? Or is there any possibility of a unified labor party?

D.A.: We would just go back to 1976 again in that case. It would fall apart. We could have been a faction in Panday’s party, but given his politics that would be a dead end. So there will be two new parties, as well as NAR. And PNM still exists — if the election were held today it would win with big African support. But 60 percent of the electorate wouldn’t vote-there is massive disillusionment.

There’s another party called National Joint Action Committee (NJAC), but they aren’t now considered to be a national contender although they played a significant role in 1970.

Elections must be held by the end of 1991, with a possible three-month extension under extreme circumstances.

Our draft platform, which will be presented at the founding convention of our party, is called “Toward A New Democracy and the Road to Full Employment.” We talk about the establishment of workers’ and people’s power through workers’ councils at the workplace, where workers could talk about what is produced and how.

We looked at Maurice Bishop’s experience in Grenada. There, the problem was that those councils never had power. The party could override them at all times.

ATC: How badly were you hurt by the catastrophe in Grenada?

D.A.: One could put it positively and negatively. There was a deep reflection afterward. Everyone had to make a step backward, given the political hysteria throughout the region. But that enabled some people to think the thing through and go forward again. We think we in CLS did that.

Of course, the working class in Grenada is very small, whereas we have a working class with a tradition of struggle — our first general strike was in 1918. We have a steel mill; we are the second largest exporter of anhydrous ammonia. We have been up against transnational corporations throughout the century.

ATC: Based on this kind of experience, your traditions and your observations of other struggles — what kind of party do you want?

D.A.: A mass party, with people who are prepared to be activists-not the traditional mass party, which is an electoral machine. We want people who will come to meetings, sell a paper, agree with the general policy and line of the party, contribute financially — but not a party whose membership is dependent on so-called deep ideological convictions of some kind. We will ensure that the workers themselves are dominant in the party.

ATC: A final question, which may be delicate because you might not want to comment on other parties in the region — but could you comment on how you see your party in comparison to the Workers Party of Jamaica, especially given its pro-Coard tilt in the Grenada tragedy?

D.A.: Our views on this are quite open and public. We have always opposed the politics of the WPJ as being frequently totally outside the realities of the Caribbean. That was demonstrated by [WP) leader Trevor] Munroe, who is as much responsible for what happened in Grenada as Coard, because he was Coard’s mentor.

[Editor’s note: Bernard Coard led a military coup from within the New Jewel Movement that destroyed the popular revolutionary government of Maurice Bishop, killing Bishop and many other leaders of the NJM. The United States was able to invade and overwhelm Grenada one week later in October 1983.] This is why the WPJ has split. Six members of the Political Bureau left the party over the same issue — not just over Grenada itself, but taking that as a manifestation of what was wrong in the party. The WPJ has lost most of its support. How their period of reflection will come out, I cannot say.

There are a number of people in the Caribbean with whom we have relations at different levels. Up to the time of our split in the ULF in the mid-1970s, the Trinidad experience was a major advance for the whole region That split obviously was a setback.

A little more about Trinidad and Jamaica. We have traditionally had much more foreign capital than Jamaica. But because Michael Manley [leader of the Peoples National Party] had power in Jamaica, a lot of people have been focusing on Jamaica. But nothing fundamental is going to take place in Jamaica for a while.

Now you can just imagine how much penetration by the CIA is going on in Trinidad! — because we have so much influence on the western Caribbean.

What has made us as strong as we are today is that we are in the mass movements. The main progressive trade-union leaders are in the CLS. That wasn’t because we planted them there — they were workers who developed radical politics.

So the real thing is to be deeply involved among the people. Once you are, there isn’t any need to get into “ism schisms,” as one of our Trinidad calypsonians sang after the sad events in Grenada.

Notes

The views of the CLS are presented in the following pamphlets published by Classline Publications (Vistabella and Port-of-Spain, Trinidad):

CLS Speaks: a Collection of Statements by the Committee for Labor Solidarity (Pre-preparatory) (1987); Keith Lookloy, Democracy in Education (1987 or 1988); Raffique Shah, Race Relations in Trinidad: Some Aspects (1988).

The program of the Oil Field Workers Trade Union can be found in the union’s Memorandum to the Government of Trinidad and Tobago (Nov. 10, 1987); and in the collection of articles Towards a New Peoples Order (1988); both published by Vanguard Publishing Company, San Fernando, Trinidad.

March-April 1989, ATC 19