Against the Current No. 19, March/April 1989

-

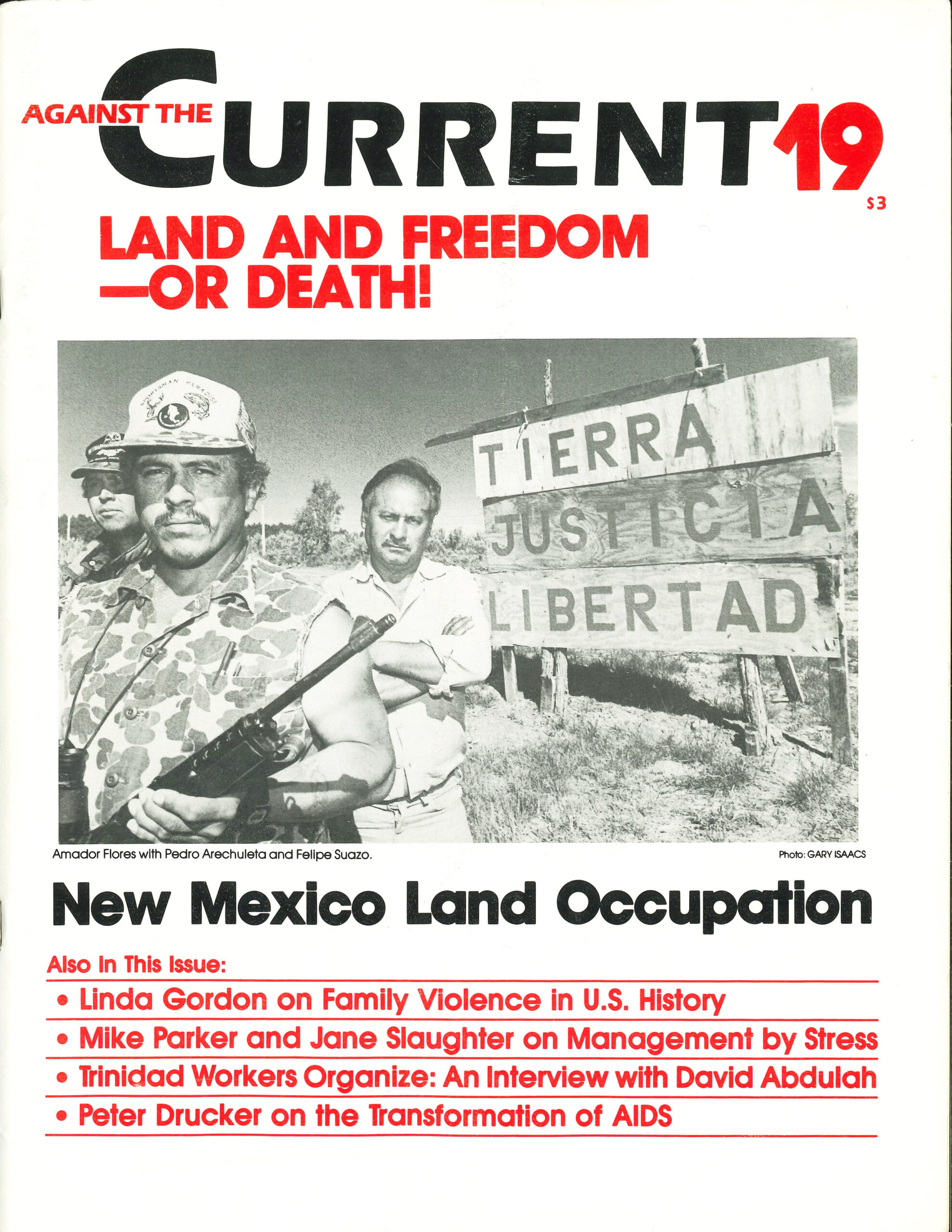

Struggling vs. Theft of Communal Lands in New Mexico

— Alan Wald - Mexican Activist "Disappeared"

-

Defending the Right to Choose

— Norine Gutekanst -

The Transformation of AIDS: Polarization of a Movement

— Peter Drucker -

The Politics of Child Sex Abuse

— Linda Gordon -

Random Shots: Wisdom of Solomon

— R.S. Kampfer - Capital Restructures, Labor Struggles

-

Free Trade . . . for Big Business

— Francois Moreau -

Management's "Ideal" Concept

— Mike Parker and Jane Slaughter -

Other Points of View

— Mike Parker and Jane Slaughter -

U.S. Labor & Foreign Competition

— Milton Fisk -

Review: Class Struggles in Japan Since 1945

— James Rytting -

Trinidad: Toward a Party of the Workers

— David Finkel & Joanna Misnik interview David Abdulah -

A Brief Glossary of Abbreviations for Caribbean Parties

— David Finkel - Dialogue

-

Reclaiming Our Traditions

— Tim Wohlforth -

A Comment on Afghanistan

— David Finkel -

Socialism from Below, Not the PDPA

— Dan La Botz -

Islam, Feminism and the Left

— Christy Brown -

A Brief Rejoinder

— R.F. Kampfer - In Memoriam

-

In Honor of Max Geldman

— Leslie Evans

David Finkel

IN READING Val Moghadam’s very informative “Retrospect and Prospect: Afghanistan at the Crossroads’” (ATC 17), I am struck by two ways in which her experiences of the debate in the left differ from mine, and perhaps from those of most ATC readers in the United States.

The first paint is her observation that “surprisingly, many on the international left continue to support the [Islamic fundamentalist] Mujahedeen. Left-wing support for the Mujahedeen has been surprising strong in Europe, where activists from London to Stockholm have defended the putative national liberation struggle.” (p.9)

Our experience in the U.S. left has been strikingly different Because the 1980s saw the final disintegration of Maoism and a certain rehabilitation of pro Moscow politics in the U.S. radical left, the dominant proclivity here (despite the dissenting voices of libertarian revolutionary thinkers like Noam Chomsky) has been apologetics if not actual praise for the Soviet Union’s military intervention in Afghanistan.

Thus, while I fully understand Moghadam’s revulsion at the spectacle of well-fed, well-educated, unveiled European leftists promoting the cause of a movement that seeks to impose illiteracy and brutal misogyny on someone else, I must confess to an equally visceral but opposite response to what I’ve read in the left press and the rhetoric I’ve heard thrown around in teach-ins where it’s customary to refer to the Afghan guerrillas as “contras” and the like.

One need only read the column of the foremost (and often brilliant in his trenchant critiques of U.S. politics) left wing journalist, Alexander Cockburn, in The Nation of June 4 or his response to critical letters in the December 19 issue to see the argument laid out.

Cockburn is an avowed partisan of the Soviet intervention – a more honorable stance, in my opinion, than that of mere apologists who refuse to take moral and political responsibility for the consequences. For Cockburn, the Gorbahev leadership’s pullout from Afghanistan as an example of “Munich in Moscow” (that is, appeasement of imperialism) in contrast to the “exemplary acts of proletarian internationalism” sponsored by Leonid Brezhnev, “who did after all preside over the consolidation of the Soviet Union as a modern industrial state, and, relatively speaking, a golden age for Soviet working class.” (The Nation, June 4, 1988)

Returning to the debate in the December 19 issue, Cockburn in consecutive paragraphs confesses to “enthusiasm for ‘revolution from without’ and the role of the external proletariat, which my original columns were indeed somewhat intended to honor,” then quotes favorably from Ligachev (Gorbachev’s chief opponent) on the ‘right of people to choose their own road and to decide on their own fate,” without the slightest sense of irony apparent.

It is my opinion that the pro-Mujahedeen leftists Moghadam has encountered and the Stalinist apologists for the Soviet invasion have more that unites them than divides them: a lack of interest in the elementary rights and suffering of ordinary people whose struggles fall outside their geopolitical frames of reference.

To be sure, the factual exposure of CIA machinations in Afghanistan — not surprisingly, mainly in support of the most fanatical factions of the Afghan resistance –in Covert Action Information Bulletin and other publications has been of use. But the politics in which the pro-Moscow left enveloped its discussion of Afghanistan, particularly the equation of Afghan resistance with Nicaraguan contras, has been an ugly disservice to the fight against U.S. intervention in Central America.

Air War against the People

One may legitimately equate the counterrevolutionary motivations of the United States government in Nicaragua and in Afghanistan. But one cannot legitimately equate the Nicaraguan contras, a U.S.-created terrorist army which has been decisively defeated because it enjoyed negligible social support, with the Afghan resistance which does tragically enjoy massive support m the countryside, including (especially!) among the poor who will ultimately be its victims.

This difference, of course, goes back to the fact that the Sandinistas came to power through a mass insurrection and created a regime of real if incomplete revolutionary pluralism, while the Peoples Democratic Party of Afghanistan (POPA) took power in a coup (a defensive one, to be sure) and sought to revolutionize society in top-down fashion.

There’s an even more painful equation to be made: that between Afghanistan and El Salvador. Of course, the revolutionary military-political Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN) in El Salvador, in which women combatants and activists play leading roles, has nothing in common with the Afghan Mu1ahedeen, who deny even medical care to women in the zones they control. But there is a deep and profound identity between the main tactics of the United States in El Salvador and the U.S.S.R. in Afghanistan: massive air war against a defenseless rural population.

The bulk of both Salvadoran and Afghan refugees are peasants displaced by rural bombing and military ground sweeps. Strikingly, the statistics in each country show about a quarter of the total papulation displaced through such methods, which I think can be legitimately labeled “state terrorism.” It’s long overdue that the left stop compartmentalizing its concerns about basic human rights into little ideological cubbyholes that blind it to this obvious and striking parallel.

. The second and most important point about Val Moghadam’s perception of Afghanistan is that she is writing as a Middle Eastern Marxist-feminist. This is a perspective to which the Western left paid far too little attention during the time of the Iranian revolution, when many of us could have avoided a great deal of political disorientation if we’d been listening.

There is nothing inherently progressive about “modernizing” dictatorships — there was certainly nothing progressive about the Shah, and I’m frankly dubious about some of the claims made for the Afghan regime’s &programs — but in the excitement of the Iranian upheaval many of us forgot that there are worse as well as better options.

Whatever political conclusions one ultimately may draw, Moghadam’s discussion of women’s rights in particular reminds us forcefully that the triumph of Khomeinism in Iran was not only a real political revolution but also an authentic catastrophe, not only for “progress” in some historical sense but for a nation of real human beings.

The victory of the Afghan Mujahedeen would be at one and the same time the triumph of a real national resistance movement and a major catastrophe for Afghan workers, women and intellectuals. The ascendance of Islamic fundamentalism to leadership of the Palestinian movement (not that I expect such a thing to happen) would be an even worse setback for the Palestinian cause than the 1967 war.

We should no more wish for the victory of such a force in Afghanistan, or anywhere in the Middle East, than we would like to see Jerry Falwell take over the United States and proclaim a Christian Republic.

A Third Camp Approach

I’d like to briefly suggest an approach for the left on Afghanistan from my own political perspective — which I realize is not shared, unfortunately, by any major forces in the Afghan war — that of revolutionary Third Camp socialism.

From this perspective, it is unthinkable as a matter of basic principle to support or apologize for a Soviet military occupation of any country, just as no circumstances permit the slightest degree of support for U.S. imperialist intervention (including U.S. backing for the Afghan Mujahedeen).

For one thing, the Soviet motivation for invading Afghanistan (a question Moghadam’s article did not address) is in no way progressive. While I think the standard Cold War interpretation that the Soviet Union moved into Afghanistan to pursue ambitions for a warm-water port is nonsense, I do think the bureaucratic ruling class in the Soviet Union seeks to consolidate its social system, which is anti-socialist and in no way in the interests of the working class or the oppressed.

For another thing, the practical consequences of the invasion are stated all too well by RF. Kampfer’s article in ATC 17: “For the next generation or two, land reform, literacy and women’s right will be associated with napalm, plastic mines and Hind gunships.”

Indeed, not only on a world scale but also inside Afghanistan, this invasion has strengthened not socialism but the most reactionary kind of politics. Time will tell if the withdrawal of the Soviet troops took place before the Afghan regime’s dependence on them had become an incurable addiction.

Does this imply that the international left ought to be supporting the Mujahedeen in defense of Afghan self-determination? Not automatically.

While it is permissible in principle for socialists to support a socially and politically ultra-reactionary national force against an imperialist invader (for ex ample, defending Haile Selassie’s slave owning Ethiopian regime against Italian aggression in the 1930s), there is no requirement that we do so if there is an alternative perspective through which national independence could be realized. Whether such an alternative exists requires a concrete and specific analysis of the given situation.

In the case of Afghanistan, I believe there is a better or at least “less bad” alternative to supporting Islamic fanatics whose victory would mean the slaughter of a large section of the population, the return of women to the Dark Ages and quite possibly the breakup of the country along lines of tribal and super power dominance.

Prior to the Soviet invasion in 19’79, when the conflict between the PDPA regime and the Islamists had the character primarily of a civil war, that is, an internal struggle even though there was of course outside great-power support on both sides, it seemed to me that socialists ought to critically support the PDPA regime, not because of agreement with its bureaucratic politics but because in that time and place its victory was the best possibility for advancing the rights of workers, women and ultimately of the rural population.

With the Soviet invasion, I think it was wrong for the left to support any side, except to demand the end of the invasion and of U.S. CIA arming of the Mujahedeen and the Zia dictatorship in Pakistan. My view today is that the withdrawal of Soviet troops will once again mean that the conflict is primarily a civil war in which we ought to be for the “victory of the PDPA — without apologizing for its complicity in the crimes against humanity committed by the Soviet invaders.

In short, I cannot agree with Moghadam that the PDPA deserved “from the international left the sort of support — and along with it, comradely and constructive criticism and advice — that, for example, the Sandinistas have enjoyed.” (ATC 17, p. 16) While many of its cadres are undoubtedly motivated by revolutionary goals and desires to advance the well-being of the people, I do not believe that as a party the PDPA’s politics and record in power cannot justify our political solidarity.

At the same time, while Moghadam’s hope that the present Afghan government may survive “and create a nonaligned, pluralist society … in which the PDPA and other left-wing and liberal parties are strong enough to craft a progressive agenda that includes rural development, workers’ rights and women’s rights” (p.9) is highly optimistic, I do think that it is the best of the existing options.

On those grounds, I hope the PDPA survives without the Soviet tanks and that the Afghan peasants’ identification of “socialism” with helicopter gunships and mass extermination can be overcome in a matter of years, rather than decades.

However, any optimism I might have is tempered by the PDPA regime’s apparent lack of steps to create serious self-defense popular militias among its own presumed social base — notably the urban working class and the pro-regime popular organizations — for a mass defense against the Islamists’ onslaught. This may be a product of bureaucratic paralysis, or perhaps a fear of which way the workers might point the guns.

March-April 1989, ATC 19