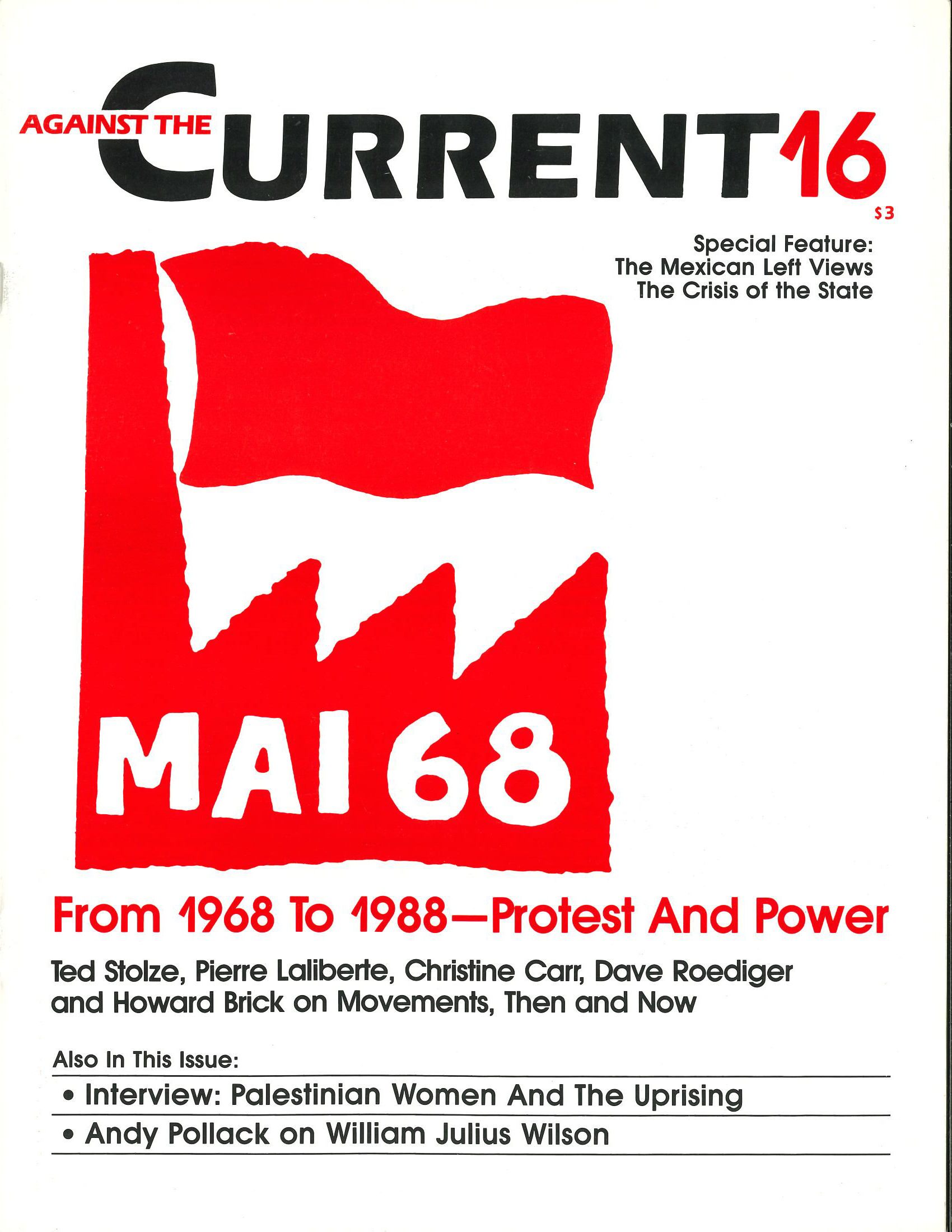

Against the Current No. 16, September-October 1988

-

The Rainbow and the Democrats After Atlanta

— The Editors -

Palestinian Women: Heart of the Intifadeh

— Johanna Brenner interviews Palestinian activist -

Critique of William J. Wilson: The Ignored Significance of Class

— Andy Pollack -

Ramdom Shots: Libs, Labs and Lawyers

— R.F. Kampfer - From 1968 to 1988

-

1968 and Democracy from Below

— Ted Stolze -

Lessons from the Campus Occupation

— Pierre Laliberté - Summary of Occupiers' Demands

-

USC Women Demand an Autonomous Center

— Christine Carr -

Something Old, Something New

— Dave Roediger -

The Participatory Years

— Howard Brick - Mexico: The Crisis, the Elections, the Left

-

Mexico: The One-Party State Faces a Deep Political Crisis

— The Editors -

The Need for a Revolutionary Alternative

— Manuel Aguilar Mora -

The New Stage and the Democratic Current

— Arturo Anguiano -

Call for a Movement to Socialism

— Adolfo Gilly and 90 others - Dialogue

-

Radical Religion--A Non-Response

— Paul Buhle -

Everyone Knows This Is Nowhere

— Justin Schwartz - An Appreciation

-

Raymond Williams, 1921-1988

— Kenton Worchester

Johanna Brenner interviews Palestinian activist

This interview with a Palestinian educator and activist on a brief visit to the United States was conducted by Johanna Brenner, an editor of Against the Current. The Palestinian’s anonymity is needed to protect her from harassment.

The discussion throws light on the central role of women in the grassroots organizations that are the heart of the Palestinian intifada (uprising) that has now continued for over nine months. Shortly after Jordan King Hussein’s announcement that he was giving up responsibility for the West Bank, the Israeli government in August outlawed the popular committees organized by the Palestinians to take control of their economic and social struggles against the occupation.

The dramatic events unfolding in Palestine make it all the more important to understand and build solidarity with the grassroots Palestinian popular movement. We’d like call to our readers’ attention to three excellent sources of information:

Al-Haq (Law in the Service of Man), P.O. Box 1413, Ramallah, West Bank (via Israel) publishes reports on human rights, Palestinian labor and other aspects of the occupation.

The DataBase Project, 22fJ S. State Street, #1308, Chicago, IL 60604 compiles extensive reports on the basis of daily accounts by Palestinian field workers. Write for a sample and subscription rates.

The Israeli League for Human and Civil Rights (P.O. Box 14192, Tel Aviv, Israel) has published a Report on the violations of Human Rights in the Territories. During the Uprising, 1988, consisting of articles translated from the Hebrew Israeli press. This essential collection can be ordered for$10 ($12 air mail). The report includes a foreword by Yosef Algazi and an introduction by Israel Shahak, the chairperson of the League.

Against the Current: Let’s start with the popular committees that were established before the beginning of the uprising.

A: Women’s committees and health-relief committees first evolved between 1968 and 1975 in the West Bank. From 1975 up to ’78 the four women’s committees, reflecting the four factions within the PLO (Palestine Liberation Organization), started working in the villages and camps mainly to mobilize women.

In trying to do this they discovered the need of women for literacy programs and for kindergartens for their children while they’re working, whether for the women’s committees or otherwise.

The interesting thing is that most of the leaders of the women’s committees at the very beginning were urban women. But they reached out to women in the rural areas, in the villages and the camps. People were not aware in general of the impact of the women’s committees. And I don’t know if the leadership outside was aware of the impact that such committees would have on a struggle like the one that we’re having now. But one must admit that not only the women’s committees but also the health-relief committees were very effective in mobilizing people in the uprising.

Superficially, it looks as though the uprising is spontaneous. As a matter of fact the background for the uprising was there. The infrastructure of having even one or two persons who are involved in one of these committees in the villages and the camps was enough to mobilize the community around him or her in that locality.

Uprising Brings Unity

From ’78 to the beginning of the uprising the results of the women’s committees’ work was felt by the local community and by the Israeli government But they were unable to do anything about the committees because their work was not publicly politicized. It took more the social-economic-development approach than the political approach.

In 1982-3 the Communist Party (CP) health-relief committee became active in serving the remote areas in the West Bank. One fact that helped in this respect was that there were so many graduate doctors who didn’t have jobs. So they formed the SP health-relief committees, first of all to give them some experience in their field and at the same time to serve the community.

The Agricultural Relief Committee is a latecomer on the scene. I think it was 1985 or 1986 that it started working. It’s a small group. Just eight or ten agricultural engineers are organizing this work.

What’s most fascinating about what happened to these groups after the uprising is their unification Before the uprising you had relief committees of the Communist Party, of the Democratic Front, of the Popular Front and of Fatah, although it was the CP that started the work.

The committees were competing with each other, each trying its best to impress on the community the effect of its work. But since the uprising, the women’s committees at least are organizing themselves as a unit. They’re not working individually; they are working more together.

Before the uprising started these committees weren’t so strong. The local communities at first tended to look with some suspicion on these committees. The Palestinian communities are a traditional society and they think that “if these are communists, we don’t want anything to do with them.”

But once they saw the social and health services being extended to the communities, they started appreciating the committees more, and the fact that the committees played a very conspicuous role in the uprising gave them more credibility.

Before the uprising some of the committee leaders were arrested and some of were put in prison. Then the second level was arrested, and the third level and the fourth level, but still the popular committees were functioning. This means that they were really entrenched in the local community. So, as I said before, although on the surface it looks as though this was a spontaneous uprising, the background was there.

Now, the role of the PLO leadership in this uprising is a subtle one. It did not plan it just this way, but it planned on building an infrastructure focused in the society through the different committees, and it is really working out very well.

ATC: Let’s talk about the committees’ role in organizing for self-sufficiency and how that plays a part in the political struggle.

A: We’ll start with the women’s committees because they’re the oldest. Even before the uprising, women’s committees were trying to organize women in the villages and camps. They started organizing them in the literacy programs, in sewing classes–the traditional functions and activities of women in Third World countries.

Through their contact with women, whether in literacy, in sewing or in arts-and-crafts activities (these were more limited), the committees worked to increase the women’s political and social awareness. So when the uprising started they had the power to reach out to the people on the grassroots level–through kindergartens, literacy programs, and some of the home-based industries.

Cottage industries exist on a very limited basis, but they’re there. They might have been successful in only three villages, four communities, but they were good examples of how a cottage industry could help to build the infrastructure and self-sufficiency.

ATC: Didn’t they try the same thing in Lebanon–to use cottage industries to support the Palestinian population economically as well as to foster independence from the Lebanese market?

A: No. It was a different experience. In Lebanon they were aiming at self-sufficiency, but not in terms of popularized cottage industry. I was in Lebanon in 1980, and you could see the economic infrastructure that had been built. There were clothing factories, sugar factories, embroidery and food factories, but they were not popularized and they were concentrated in Beirut.

So after the invasion (1982) these were destroyed and they couldn’t be picked up again. The difference is that in the West Bank the industry is not localized, it’s spread all over. At least the aim is to spread it all over.

The uprising helped encourage this approach to cottage industry because people started boycotting Israeli products, at least the products they can get from local sources. And it’s becoming a national call People are urged to boycott Israeli products and look for alternative products that are locally made, produced by Palestinians, even if they are lower in quality.

Now the Agricultural Relief Committee started working before the uprising with the farmers, helping them to overcome some of their difficulties by means of irrigation, use of pesticides and marketing techniques.

They did not reach out to a big group of farmers. Their work was mainly concentrated in the Jordan valley where most of the vegetable fanning was. Since the uprising, quoting the words of one of the people from that committee, “What we have accomplished in five months we would not have accomplished in ten years if we were using the same methods we were using before.”

There was a need; people were ready. Even in the camps where they have very limited areas there are small gardens where people grow their own vegetables and produce and raise animals–chickens or goats or whatever.

In the villages, because of the migration of many of the farmers to work in the Israeli labor market, the land had been neglected for fifteen or more years. Now people are going back because some of them are boycotting working in Israel, and some of them were forced out of work. The Agricultural Committee is really taking good advantage of this to guide and counsel them in ways and means of farming their own land.

ATC: How have the curfews and the ability of the Israelis to cut people off from their access to food affected this attempt at self-sufficiency?

A: People under curfew had the money but they didn’t have access to buying food stuffs. So after two months of the uprising, they picked up on planting their own vegetables and trying to be self-sufficient at least in vegetables. Otherwise in Palestinian houses you find food stored from one year to the next, whether it’s olives, cheese, wheat, beans, rice, flour. They’re not cut off from these.

In the villages the popular committees are also cultivating unused land, and it’s well known that the produce is going to be used by the whole neighborhood. Even if the committee comes to a house with a big garden and helps in cultivating the land it says, “You use the produce, but your neighbors will be able to get some of the produce too.”

ATC: It’s understood that people are going to share?

A: We haven’t seen the result so far, so I’m not sure, but this is the understanding, at least among the committees. This is a viable way of raising socialist concepts too, of collective work without indoctrinating people-people are practicing it before theorizing.

ATC: You had mentioned that the agricultural committees were helping people to find a certain kind of goats?

A: This is a Middle Eastern goat that doesn’t need inoculations or the kinds of care that other goats need. They were experimenting with this kind of goat even before the uprising, and now they are using it. A pregnant goat is taken to a village and given to one family. After it gives birth to the kid, it is impregnated again and given to someone else. The same thing is being done with chickens. They’re using local carpenters and blacksmiths to make cages and selling them for very low cost. They are teaching people how to use simple incubation methods to produce more eggs.

ATC: And this is all being done through the agricultural relief committees?

A: The agricultural relief committees are working now with the local popular committees because they cannot reach out to everybody. But through the popular committees they’re reaching 150 committees. They’ve been able to plant 250,000 vegetable seedlings, and they’re in the process of bringing it up to half a million seedlings. And they were able to cultivate almost 10,000 dunums [slightly less than an acre] during the uprising. These are all around the houses mainly; we’re not talking about big fields.

ATC: What about in the cities?

A: They’re reaching out to the cities. Usually people would grow roses or flowers. My aunt had to cut some of the trees to plant vegetables, but she is now planting her own garden. My mother is planting her own garden. Friends of ours have their own rabbit cage and a goat. So we’re talking about city people.

A Cooperative Movement

ATC: Why don’t you talk a little bit about some of the cooperatives that have been organized: sewing, food processing.

A: The Surief Co-op is a traditional example. In this village in the Hebron area, the Mennonite Central Committee has been encouraging women to produce Palestinian embroidery for over twenty years. The Mennonite Central Committee would sell their products locally and abroad.

In 1978, I think, a Palestinian woman started working with the women in this village to organize themselves into a cooperative. Instead of depending on the Mennonite Central Committee they would market their embroidery themselves. They would buy the materials and the thread, and they themselves would distribute it.

They have been very successful. It’s one of the very good examples of women cooperatives. But it’s still traditional, and it doesn’t have such an impact on the community because it was done through a foreign agency.

ATC: Who makes the decisions in these cooperatives?

A: Now the women are making decisions. They decide how much to pro duce, and they have total control over what they do.

The other women’s cooperative that is very successful was organized by one of the local women’s committees. It does food processing in Biddo. Two people, one Dutch, I think, and the other a local dietician, researched the market for the cooperative, comparing the possibilities for the cottage industry in Gaza and in the West Bank. They found it very difficult to work in Gaza so they started working in the West Bank. They produce mainly pickles which are very popular in the local markets.

After the uprising, due to the need to support the local products and to pro mote self-sufficiency, a small group of urban activists got together and discussed what they all felt should be done. Most of the committees are made up of independent activists, but the different political factions are represented.

The first project was listing all the local products and where people can buy them in a pamphlet just like the yellow pages. For example there were certain things that I didn’t know were produced locally, so we thought that would be a good way to encourage people to buy locally.

Then the committee thought of how we could encourage and initiate cottage industry. We targeted Abu Ghosh, a village near Birzeit, to encourage them to produce dresses, skirts and blouses for children and women, to counteract the Israeli products. It would not be able to replace all the Israeli clothing products, but at least it would help the local and nearby people in this respect.

We started with three women; we visited them and discussed the possibility. At the beginning they didn’t really buy the idea. They said they couldn’t do it, they didn’t have the know-how, they didn’t know how to cut dresses.

A local designer in Bethlehem volunteered to give them patterns for some of the pieces, and another local committee was able to lend them some money. But to borrow the rest of the money was a big problem for them, because it was the first time in their lives that they were borrowing money from an institution. So one of the members of the committee went with them to countersign the loan.

They bought the material and they rented sewing machines for the first batch. If it works out, then they will buy their own, at least one, good industrial sewing machine.

This whole idea developed too because women in the villages were exploited by the Israeli market. Materials are sent to the villages where women sew them into dresses and send them back. They are paid minimum wages for that. So instead of doing it for the market they can be doing it for themselves.

ATC: They do piecework for the Israelis?

A: Yes. It is very common wherever we go in the West Bank and in Gaza. When I was working at the vocational training center we used to send the girls from the dressmaking and sewing classes to be trained in some of the factories. They’re called factories, but really they are sweatshops where women work for Israeli firms.

I’m going back to a committee that is trying to initiate an interest in cottage industry. We’re experimenting with baby food that’s cheap and could be available for mothers to use under curfew or under siege, because sometimes they are under siege.

The formula is simple: chick peas and ground wheat that can be used either with water or with milk, sweet or salty, or with vegetables for that matter. It’s still in the experimental stage; we haven’t tried it out yet. One of the members of the committee is a dietician and she is working on it.

She is also working with two other people on producing a leaflet with simple recipes that are medically adequate diets for children and for the family under siege. She uses some of the foodstuff families keep in the house: chick peas, beans, lentils.

The Politicizing Process

ATC: Could you say a little bit about how you think this work involving women and men in the project of self-sufficiency contributes to the development of political consciousness? H= do you see that fitting in with the broader struggle?

A: It’s looked upon by people now as part of building the economic infrastructure of the Palestinian community under occupation as a first step towards independence. Once you are economically independent then political independence will follow. And on the other hand it’s to prove to the Israelis that we are a viable society.

But while building this infrastructure I expect people to learn how to work in collectives, how to organize themselves, how to coordinate work with the various committees. The uprising has proved to be effective in promoting these things. The Palestinian factions were at each other’s throats all the time, and all of a sudden they came together and they’re working in coordination now.

ATC: ls this a way of reaching new people and bringing them into the struggle?

A: It’s really spreading like anything among people. People who never were politicized now at least feel that we have the power, we can d0o it. It is really activating most of the people; the most passive among them are being involved now, some of them not actively, but at least they support what is happening. In my opinion this is one step towards being active. Take my mother, for example, and my aunt who are really trying to establish their own gardens and be able to support themselves. It’s one way of politicizing them.

You go to the grocery shop and now you find that on the shelves are “locally produced products.” You never saw this before. So now people don’t have to go around and look; they just go to that shelf and buy what they want, detergent, food stuff, whatever.

ATC: Let’s talk about this issue of women’s participation in both the popular committees and these co-ops and how that’s affected them. You mentioned for example that rural women were reluctant to borrow money and take on that responsibility, but if they wanted to do the co-op they had to, so they were forced to take up new responsibilities and new ways of doing things.

A: I think that if we succeed with the cooperative in Abu Ghosh and with the baby-food cooperative, then these could be good examples for other women We’re very keen for this project to succeed in Abu Ghosh, because then we can carry it forward to other areas not necessarily in sewing but in other cottage industries.

The committee is well aware of the importance of empowering women to take an active role in the decision-making and in the way they want to carry on with this project. They might come up with new ideas that we don’t think of because they know what the need of the local community is. If this project succeeds, like the one in Biddo, I think it will show that, given the opportunity, women can take over some of these responsibilities.

As to the women’s committees, they were active even before the uprising, but they were reaching out to young women. During the uprising, they could start reaching out to older women.

Older women have been active politically and in the streets because it was easier for old women to go into the street and throw stones or defend some of the village kids than for an 18- or 20-year old. I know of two incidents. A woman saw one of the boys running from the soldiers and she caught him and said, “Why are you late? We have an appointment with the doctor.” She took him to one of the second-story buildings in Ramallah and that’s how she helped him escape.

In another incident where a boy was running away from the soldiers, a young woman grabbed him and said, “We had a date. Why are you late for the date?” and she—you know-acted up to him. So these are indications of women’s involvement in the whole struggle.

In Jerusalem every Friday after prayers the demonstration that is becoming routine is always led by women in the mosque. These are very traditional women who are going to the mosque to pray, and after that, they come out demonstrating, singing, raising the Palestinian flag and throwing stones at soldiers.

You can see it in Jerusalem and you can see it in Nablus, Ramallah, Bizzeit and in Gaza. I can only say that from my observations; no research has been done on this subject. But on the face of it you can see women actively participating.

ATC: can you say something about women’s leadership?

A: The women’s committees, like all the other committees, were active and effective in organizing the popular committees, so indirectly there are leaders, but you cannot pinpoint one person or a few persons, women or men. We know that there are leaders, but they are not doing it publicly.

For example, in the committee that is trying to initiate the co-ops, four out of seven are women In agricultural relief, although all are engineers, there are two very active women. In the health-relief committees, among those I know, there are three active women. And when I say active women I mean they are really aware of the importance of creating this awareness within the women they work with.

A month ago I was at a workshop attended by many people from the health services, the agricultural relief services, the women’s committees, the Palestine counseling center, and so on. This workshop was intended to train counselors to guide mothers and families in health, in agriculture, in education, in social work and in family planning.

Of the thirty-five people in that workshop, only five were men–the rest were women. I was surprised myself. They’re very active women. Many issues were raised on family planning, on the traditional Palestinian family and traditional Arab family and how women counselors could help mothers become empowered to make decisions at home and otherwise. This was an extremely interesting workshop.

ATC: Let’s talk a little bit about the issue of education with the schools closed down.

A: Since schools were closed there have been increasing complaints from the children and their families as to what’s going to happen to our children’s education if this uprising continues. And everybody wanted this uprising to continue as long as possible.

Because of the continued complaints from the families, the popular committees organized popular education. It started in mosques, in churches and, even more, in homes. Mothers would start their own classrooms. Some of these women had never been teachers in their lives, but they took upon themselves to group children from their neighborhoods and start teaching them.

They didn’t have the materials, they didn’t have the space, and they didn’t have the program. They would just pick up any text book and start teaching. So, at the Early Childhood Resource Center we thought that since the kindergartens are closed and our work has been to some extent disrupted, we might as well help in preparing some packages to help these popular committees in teaching.

We wanted to help them teach in a different way, through dialogue, through self-learning and self-reliance.

We tried out one package. Since the whole issue of agriculture has been raised, it would be the theme for the package and would be treated in the different disciplines, in language, art, science and mathematics. Now if the schools are opened this material can be used in schools too.

This is a continuation of our basic program in the Early Childhood Resource Center. We’re trying to present at least preschool education with an alternative approach–that of empowering children in their learning and promoting their ability to think for themselves, to think analytically and objectively and to be able to work with teams and groups of other children as a basis for later stages in changing the education system.

We’re trying to provide alternative programs, alternative curriculum, and alternative methods of teaching.

One of the things we faced in working with kindergartens is that in many kindergartens teachers are teaching the children patriotic songs. Our concept was to create awareness of their social and political situation among the children without indoctrinating them.

We made a tape based on the program of the Early Childhood Resource Center. Many of the songs were written by a member working there, and the music was by a Palestinian musician. Some of the songs are popular folklore tunes that were sung in Palestine. All of them have Middle Eastern music and instruments. The concept of the songs is to prepare the children to resist the occupation, through love of the land, love of the traditions and of the olive tree–a symbol of the struggle.

September-October 1988, ATC 16