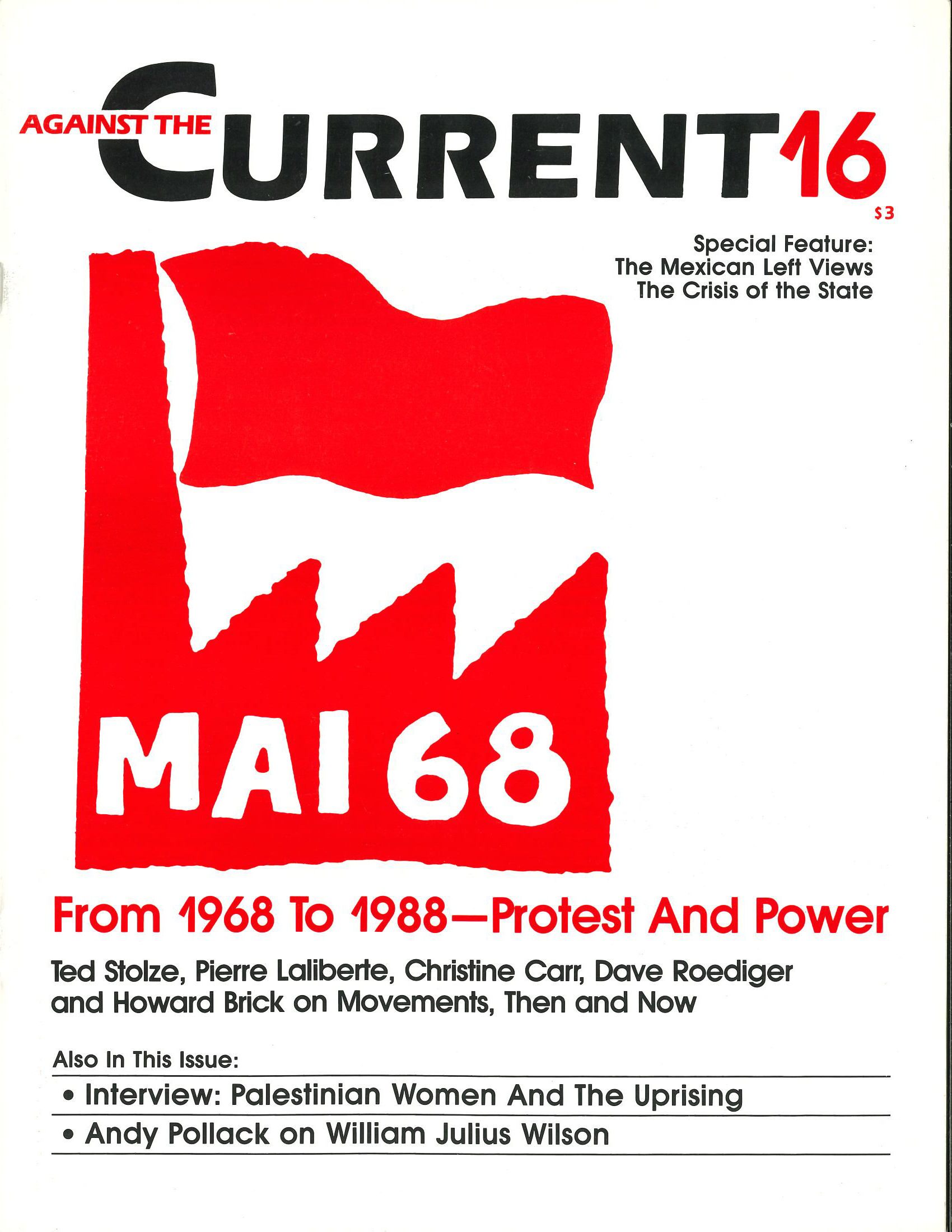

Against the Current No. 16, September-October 1988

-

The Rainbow and the Democrats After Atlanta

— The Editors -

Palestinian Women: Heart of the Intifadeh

— Johanna Brenner interviews Palestinian activist -

Critique of William J. Wilson: The Ignored Significance of Class

— Andy Pollack -

Ramdom Shots: Libs, Labs and Lawyers

— R.F. Kampfer - From 1968 to 1988

-

1968 and Democracy from Below

— Ted Stolze -

Lessons from the Campus Occupation

— Pierre Laliberté - Summary of Occupiers' Demands

-

USC Women Demand an Autonomous Center

— Christine Carr -

Something Old, Something New

— Dave Roediger -

The Participatory Years

— Howard Brick - Mexico: The Crisis, the Elections, the Left

-

Mexico: The One-Party State Faces a Deep Political Crisis

— The Editors -

The Need for a Revolutionary Alternative

— Manuel Aguilar Mora -

The New Stage and the Democratic Current

— Arturo Anguiano -

Call for a Movement to Socialism

— Adolfo Gilly and 90 others - Dialogue

-

Radical Religion--A Non-Response

— Paul Buhle -

Everyone Knows This Is Nowhere

— Justin Schwartz - An Appreciation

-

Raymond Williams, 1921-1988

— Kenton Worchester

Ted Stolze

THE YEAR 1968 was the crest of a worldwide wave of political radicalization and struggle against both capitalism and bureaucratic socialism.(1) Yet contrary to the way it is often depicted in the mainstream media, 1968 was neither an historical accident nor a miraculous eruption that we can sadly or thankfully (as the case may be) put behind us from the safe distance of twenty years. In fact, 1968 was only the latest in a long series of challenges to the dominant social order.

We can see 1968 as the high point in the period of upsurge that began around 1959-60 with the Cuban revolution and Algerian civil war, and ended around 1974-75 with the defeat of the Portuguese revolution. In addition, although the struggles around 1968 have subsided, they have certainly not disappeared: the crises of both capitalism and bureaucratic socialism continue in 1988.

In this article I hope to explain as succinctly as possible the origins, uneven development, and precipitous decline of those movements for social change that shook the ’60s and require those on the left to engage in neither nostalgia nor uncritical admiration but careful study. Leftists must strive not only to analyze the often dismal present and argue for a better future; they must also scrutinize and learn from the successes and failures of the past.

The difficult but crucial task today is to discern not just what was unprecedented about the struggles of the ’60s but also to suggest what might continue to be their relevance for the struggles of the ’80s and ’90s.(2)

In order to understand the struggles of the ’60s, we have to locate them within the larger framework of the post-World War II economic boom and international capitalist expansion.(3) In addition, we have to grasp the nature of the forces that eventually combined to disrupt the long period of sustained growth and stability that accompanied the emergence of the United States as the world’s dominant economic and military power.

Certain contradictions inherent in the boom made it possible for such lesser powers as West Germany and Japan to benefit from, for example, the new military build-up without having to bear as great a burden as the United States. This permitted rates of growth in those countries which eventually enabled them to undermine U.S. hegemony in the world economy.

This perceived threat to continued U.S. world dominance was without doubt a significant factor in Presidents Kennedy and Johnson’s decisions to escalate the war in Vietnam. But of course an unintended consequence of that escalation was the consolidation of anti-imperialist struggles across the globe.

The boom subsequently unleashed a remarkable process of industrialization, urbanization and proletarianization, which resulted in the rapid transformation of the social structure on a world scale.(4) Especially in the more backward sectors of advanced capitalism, for example, in the southern regions of both the United States and Western Europe, old ways of rural life were steadily eroded. Yet this so-called “modernization” often meant little more than the creation of new elites while the majority of the new urban population continued to live under conditions of extreme poverty.

The groundwork was laid for the emergence, in the late ’60s and early ’70s, of working-class militancy and revolts against the kinds of authoritarianism that had flourished under the old order. For instance, the struggles of poor and working-class Blacks against racism in the United States should not be viewed in isolation from similar anti-authoritarian struggles in France, Italy, Portugal and Spain.

Finally, the boom swelled the ranks and worsened the social conditions of students across the world.(5) By the ’60s most students were no longer the privileged children of the ruling class but increasingly came from lower-middle and working-class backgrounds.

It is important to recall that the economic boom of the post-World War Il period was equally a baby boom. In the United States, the number of students at four-year colleges doubled by 1960, compared to the pre-war period; between 1960 and 1985, the number rose another 70 percent. The situation was similar in Western European countries: between 1950 and 1964, the number of students in universities tripled in France, doubled in West Germany, increased by 60 percent in Britain and 50 percent in Italy.(6)

Many students came to realize that the real purpose of their education was neither scientific inquiry nor critical reflection but preparation for later lives as purveyors of technocratic ideologies that were intended to foster and sustain the myth of a supposedly conflict-free and permanently expanding capitalist system. When those ideologies came into conflict with the experience of an increasingly sterile and alienating society that failed to meet basic human needs, students were often thrown into intellectual turmoil and responded with moral outrage.

Let’s also not forget that around these students, and youth in general, arose an entirely new market and culture, which involved everything from cosmetics and toiletries to cinema, television and music. In Western Europe and the United States, consumerism made possible new kinds of personal relationships, awakened youthful desires, and made it possible for young people to break with their parents’ lifestyles.

There’s no question that all this was an attempt to integrate youth and students all the better into bourgeois society, but the effort was at least partially in vain. In many respects the social space that was opened by late capitalism was simultaneously reappropriated by teenagers through their own creation of a distinct youth culture. For example, the slogan “sex, drugs and rock-n-roll” captures the degree to which youth rebellion against traditional values emerged as an oppositional movement within the culture of consumerism itself.

There was nothing predetermined about the precise ways in which struggles happened to break out in the ’60s–particularly following the bleak period of the ’50s in which external repression only hastened the already apparent internal disintegration of the old left. After Stalin’s death in 1953 and the events of 1956 that included both Khrushchev’s “secret speech” to the Twentieth Congress of the Soviet Communist Party and the brutal suppression of the Hungarian Revolution, crimes committed in the name of “socialism in one country” could no longer be rationalized or ignored.

At the same time, the old left seemed unable to explain why capitalism didn’t collapse after the war but enjoyed its greatest period of resurgence. Tragically, as hundreds of thousands of disillusioned people left the various Communist parties around the world, other socialists, Trotskyists included, found themselves unable (or unwilling) to offer an attractive alternative.(7)

Yet I don’t want to exaggerate the extent to which the old left was cut off from an incipient New Left. Good cases in point in the United States are the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS).(8)

Both SNCC and SDS included within their ranks a core of people who in the ’50s had either been in or close to the Communist Party, the Shachtmanite Independent Socialist League (the successor to the ’40s Workers Party), or the Socialist Party. Often such persons had been involved in the youth groups of those organizations and had left because of what they regarded as hopelessly sectarian doctrine and debate. It’s difficult, then, to appreciate fully the painful births of SNCC and SDS without taking into account their connections to the old left, however limited and precarious those connections might have been.(9)

SNCC and SDS tried to go beyond the limitations of previous socialist theory and practice; they self-consciously sought to reinvent the democratic spirit of social struggle by criticizing and avoiding a repetition of what seemed to them to be intolerable about the old left: bureaucratic organization, obsession with the purity of doctrine and jargon-ridden prose. No doubt this was a caricature of what had been the case–if not for communists, at least for revolutionary socialists. But caricature or not, these new activists had a point: why would a person want to participate in a popular movement or join a leftist organization unless she could be certain that her voice would be heard, that her experience and ideas would matter?

SNCC was able to lead civil rights struggles and SDS was able to build a student movement because both relied not on given political channels but worked outside of traditional party politics. Even though there were individuals within SNCC and SDS who advocated a “realignment” within the Democratic Party, in neither organization was there ever simple reliance on the apparatus of the Democratic Party; there was instead a growing awareness of, and confidence in, the power of grassroots organizing and coalition building. By the end of the ’60s heightened resistance to racism at home and the Vietnam War abroad intensified the radicalization of SNCC and SDS and moved them even further away from bourgeois politics.

SNCC’s vision of the “beloved community” and SDS’s conception of a “democracy of individual participation” evidenced their mutual recognition that political power comes not from elections or lobbying but from people taking matters into their own hands. Members of both organizations argued that only democratic self-activity and forms of direct action enable persons to change society.(10)

Across the world, students and workers discovered previously unimagined resources of solidarity and powers of collective initiative and creativity. The ’60s in general and 1968 in particular simply cannot be understood apart from an international raising of revolutionary-democratic demands; from New York to London, Paris to Prague, Rome to Berlin, Mexico City to Warsaw, both capitalist and bureaucratic socialist societies were shaken to their foundations.

Consider the French events of May-June 1968.(11) Student rebellion and street fighting triggered the largest general strike in history: for nearly two months the country was paralyzed and Charles De Gaulle’s government was dazed as almost 10 million workers seized control of the workplaces.

But socialist revolution did not occur in France, and indeed the crisis was resolved almost as quickly as it had arisen. Despite the militancy and enthusiasm of those on strike or demonstrating in the streets, the French Communist Party (PCF) and its union of influence, the General Confederation of Labor (CGT) did not provide revolutionary leadership. The largely student-based far left was too small and isolated from the working class to take over when the PCF and CGT hesitated. In addition, De Gaulle masterfully divided and disoriented people even further by calling for elections and granting a few concessions. Before anyone realized it, the huge upsurge had slipped through the fingers of the French left.

Almost simultaneously Czechoslovakia, the so-called “Prague Spring,” which from March to July of 1968 had lifted hopes for the realization of a “socialism with a human face,” was suppressed in August by Soviet troops.(12) Students and intellectuals had put too much faith in the ability of the liberal Dubcek government to enact reforms from the top; and massive demonstrations in October and November (and several times in 1%9) to protest the Soviet invasion never coalesced into a working-class opposition that could act as a united force to seize power from below.

When we turn to the United States, it’s clear that the civil rights and anti-war movements never approached the level of struggle characteristic of France and Czechoslovakia. In 1968, the more modest question of power for the U.S. left had to do with whether the Democratic Party could serve as a vehicle for progressive social change, not with any immediate prospect for revolution. Yet many on the left lost patience with the slow process of building a third political force that would be independent of both Democratic and Republican parties, and either entered the Kennedy or McCarthy campaigns or deluded themselves that revolution could be achieved by sheer force of will.

A large number of newer members of both SNCC and SDS had already turned to Marxism. Yet their conception of Marxism often was no more than an eclectic combination of Stalinist dogma and excessive enthusiasm for guerrilla warfare in the Third World. As a result, many on the left came to regard the U.S. working class not as a slumbering but as a comatose giant, incapable of being roused to lead anti-capitalist struggle.

Numerous substitutes for the working class were devised: students, intellectuals or certain marginal groups were now supposed to accomplish what workers could not or would not do for themselves. Such substitutionism proved to be a huge barrier to any real strategy to deal with racism, sexism, imperialism and other forms of oppression.

There are two reasons for this shortcoming. First, all these oppressions are rooted in and sustained by capitalist relations of production. Under capitalism, class exploitation is the general thread that ties together numerous specific forms of domination.

Second, it’s impossible to unify the struggles against these oppressions without setting into motion the social force that can most effectively confront the capitalist ruling class. That social force is the working class, the vast majority of the population, organized in factories, offices and communities.

Now some sections of the left were in fact critical of other radicals’ romanticization of the Third World and tried to make a tum to the working class in the late ’60s and early ’70s, but even these sections suffered from a great deal of political confusion. Those on the left who recognized the revolutionary potential of the working class in the advanced capitalist countries–particularly in light of May ’68 in France and Italy’s Hot Autumn of 1969–still abstractly conceived of the working class as a kind of homogeneous whole.

They overlooked the extent to which the real working class is heterogeneous and divided along regional, sectoral, industrial, racial, ethnic and sexual lines. They too quickly forgot that it was precisely the ’60s movements–first against racism, then against imperialism and war, finally against women’s oppression-that provided the means to reach a divided working class.

In most countries, but especially in the United States, the working class had been relatively quiet during the ‘5Os and early’60s. By the early ’70s, however, workers were beginning to demonstrate in a dramatic series of rank-and-file battles and wildcat strikes their capacity for radical activity. The post-war boom was coming to an end, and the international economic situation was beginning to worsen. The newly elected Nixon administration wasted little time before it set into motion a “New Economic Policy” that would prove to have serious consequences for the living standards of millions of U.S. workers.

In response, workers revolted on the shop floor against speed-up and deteriorating working conditions. More generally they spoke out against a social crisis that was dramatically undermining the overall quality of their lives. Here I have in mind such broad industrial struggles as the national Teamster wildcat strike of 1970, the 1972-73 battles in Norwood, Lordstown, and St Louis against the General Motors Assembly Division (GMAD); the massive strike upsurge by public service workers; and the fights led by Black autoworkers in and around the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM) and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers.(13)

It is crucial to observe that in many respects these eruptions of rank-and-file militancy, particularly on the part of young workers, were triggered by the anti-war and Black power movements of the late ’60s. A general social and political climate of activism and resistance had a dramatic impact on certain layers of the working class.

Two decades of prosperity rapidly drew to a close. But so too did democratic, broad-based, grassroots movements fragment under the pressure of altered social conditions and increased repression under the Nixon administration. The newly emerging Black revolutionary movement was crushed by state assassinations and frameups. As the left’s defeat became evident, some radicals turned to terrorism, some to party-building, but most dropped out of politics altogether. With the notable exception of the women’s movement, the ’60s upsurge was over.

Twenty years after the peak of that upsurge, while leftists patiently organize and prepare for another period of mass radicalization, what lessons can they learn from the victories and defeats? There are four points that I’d like to make.

First, at their best, the movements of the ’60s were profoundly democratic and made it possible for ordinary people to participate in politics in exciting and powerful new ways. Leftists should embrace democracy as essential to any new society worth fighting for.

Second, social and political struggles are limited in what they can accomplish when they exist only as opposition movements. Eventually the question of power arises. At this point only a well-organized and combative working class can provide direction. Leftists should always insist that full political and economic democracy can only be achieved as the result of the self-organization and direct action of the working class.

Third, it is precisely the social movements that make it possible to approach a divided working class, which, despite rumors to the contrary, is not disappearing but is involved in a dramatic worldwide process of recomposition and restructuring.(14) Just as the various oppressions under capitalism are not reducible to class exploitation, so too these movements are not reducible to class struggle. Leftists should participate in and help to build these movements not just as means to reach a heterogeneous working class, but as ends in themselves.

Fourth, revolutionary organization is vital to insure the continuity of political struggle during times of deradicalization and demoralization, even if today these organizations represent only a small minority in both capitalist and bureaucratic socialist societies. Leftists should realize that our present marginality makes it even more important that within our ranks we preserve internal democracy and keep leaders accountable to the entire membership. Otherwise, the left risks lapsing into the complacency of forever drawing lessons from the past without hope of providing leadership in the present and vision for the future.

At the heart of the turmoil of the ’60s in general, and 1968 in particular, was a revolt against everyday capitalist and bureaucratic socialist misery: the little anxieties and indignities suffered that mount, almost imperceptibly at first, until finally they explode in a collective desire for change. What men and women, young and old, Black and white, students and workers experienced in the streets, at the barricades, and in occupied factories, offices and universities was the possibility and the necessity for a completely new kind of society.

The memory of those years and those struggles remains capable of seizing the imagination in order to proclaim that things don’t have to be as they are, that our lives can and must be different, that if we don’t change society for ourselves, someone else will more than gladly do it for (or against) us. The left should reclaim for itself the confident slogan that echoed through the streets of Paris in May 1968: “It’s only a beginning, let’s continue the fight!”

Notes

- My deepest thanks to the following comrades and friends for their comments and criticisms: Bob Brenner, Warren Montag, Wayne Rothschild, Peter Landon, David Finkel, Joe Lunch and, especially, Elizabeth Leonard.

back to text - I am indebted to Chris Harman’s excellent analysis in The Fire Last Time: 1968 and After (London: Bookmarks, 1988) for my general perspective in this article, even though I disagree with some of his conclusions.In particular, I take exception to Harman’s tendency to disparage ’60s-style a movementism” (351-55) in favor of what seems to me to be a rather abstract class politics. I regard the new social movements not as distractions from reaching out to the working class but precisely as a means (not the only one, of course) for the left to approach a heterogeneous and divided working class.

back to text - On the underlying causes of the post-war boom and its collapse in the early 70s, see Chris Harman, Explaining the Crisis (London: Bookmarks, 1984), especially pp. 75-121. Harman focuses on the new “permanent arms economy” as the key factor. For a quite different explan tion of the long-term decline of U.S. competitiveness in the world economy, see Robert Brenner, “How America Lost the Edge: The Roots of U.S. Economic Decline,” Against the Current 2 (1986), 19-28.

back to text - Harman, Fire 15-37.

back to text - Harman, Fire 38–54. On the student movement in general, see the following remarkable oral history: Ronald Fraser, ed., 1968: A Student Generation in Revolt (NY: Pantheon, 1988).

back to text - These figures are from Fraser, 76.

back to text - On the isolation of the U.S. left in the ’50s see Maurice Isserman, lf I Had a Hammer … The Death of the Old Left and the Birth of the New Left (NY: Basic Books, 1987).

back to text - On SNCC, see Clayborne Carson, In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s (Cambridge, MA: Harvard, 1981). Although for many years the standard work on SDS has been Kirkpatrick Sale, SDS (NY: Vintage, 1973), the following recent book provides a much better account of the early political discussions within SDS: James Miller, Democracy ls in the Streets: From Port Huron to the Siege of Chicago (NY: Simon & Schuster, 1987). Miller’s book has the entire “Port Huron Statement” reprinted as an appendix. Other valuable primary documents from the histories of both organizations can be found in Judith Clair Albert and Stewart Edward Albert, The Sixties Papers: Documents of a Rebellious Decade (NY: Praeger, 1984).

back to text - On the continuity between the old left and the New Left, see Isserman, 173-219.

back to text - Yet both SNCC and SDS were notoriously undemocratic with regard to women’s participation in their own organizations. It is sad but essential to recall that the women’s movement had to tum the argument that “personal is political” (staunchly defended by male members of both SNCC and SDS) inside out for their own use. See Sara Evans, Personal Politics: The Roots of Women’s Liberation in theCivil Rights Movement and the New Left (NY: Vintage, 1979).

back to text - In my view, Daniel Singer’s long out-of-print Prelude to Revolution: France in May 68 (NY: Hill and Wang, 1970) remains the definitive account But see Harman, Fire 84-120, and Ernest Mandel’s The Lessons of May 1968,” New Left Review 52 (1968).

back to text - On the “Prague Spring,” see Harman, Bureaucracy and Revolution in Eastern Europe (London: Pluto, 1974), 188-241.

back to text - For a discussion of labor militancy in the early ’70s, see Daniel Guerin, 100 Years of Labor in the USA {London: Ink Links, 1979), 227-49. On DRUM and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, see Dan Georgakas and Marvin Surkin, Detroit: I Do Mind Dying (NY: St. Ma tin’s 1975).

back to text - See Alex Callinicos and Chris Harman, The Changing Working Class: Essays on Class Structure Today (London: Bookmarks, 1987). On the international context for this restructuring of the working class, see Joyce Kolko, Restructuring the World Economy (NY: Pantheon, 1988).

back to text

September-October 1988, ATC 16