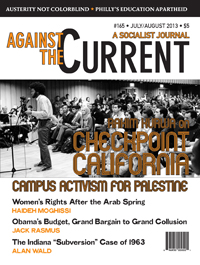

Against the Current, No. 165, July/August 2013

-

Obama: Human Rights Disaster

— The Editors -

Austerity Is Not Colorblind

— Malik Miah -

Defending Public Education in Philadelphia

— Ron Whitehorne -

Update: Chicago's School War

— Rob Bartlett -

BDS Campaign Sweeps UC Campuses

— Rahim Kurwa -

Inside the Corporate University

— Purnima Bose -

Changing Ecology and Coffee Rust

— John Vandermeer -

Austerity American Style (Part 1)

— Jack Rasmus -

Arab Uprising & Women's Rights: Lessons from Iran

— Haideh Moghissi - On Assata Shakur

- Fifty Years Ago

-

Remembering Medgar Evers

— John R. Salter, Jr. (Hunter Gray) -

The Indiana "Subversion" Case 50 Years Later

— Alan Wald - Reviews

-

Marxism and "Subaltern Studies"

— Adaner Usmani -

Palestinians and the Queer Left

— Peter Drucker -

A Novel of Class Struggle & Romance

— Ravi Malhotra -

The Radicalness of the Accessory

— Kristin Swenson -

The Implacable Russell Maroon Shoatz

— Steve Bloom - In Memoriam

-

Howard Wallace, 1936-2012

— Sue Englander

Rahim Kurwa

Download the PDF of this article.

The 2012-2013 academic year has seen seven University of California campuses launch campaigns to divest university funds from corporations enabling oppression of Palestinians. This essay outlines the roots of the campaign, its progress, and the pressures facing activists working to support Palestinian rights. For background on the broad BDS (boycott/divestment/sanctions) movement, see “A BDS Movement that Works” by Barbara Harvey in ATC 161, http://www.solidarity-us.org/node/3720.)

WHILE THE FIRST divestment campaign at the University of California dates back to 2001 at UC Berkeley, the current wave of divestment activism has grown significantly in the aftermath of Operation Cast Lead in the winter of 2008-2009. This Israeli assault on the Gaza Strip resulted in roughly 1,400 deaths, among whom a majoritywere civilians and 308 were minors. Among the civilian infrastructure destroyed were eighteen schools, 3,540 housing units, 268 private businesses, mosques, hospitals, and a bevy of United Nations refugee aid projects.

Major reports by Human Rights Watch, the UN and Amnesty International revealed serious evidence of war crimes and crimes against humanity. Recoiling in horror from what it described as 22 days of death and destruction, Amnesty International called for a comprehensive arms embargo on Israel, as a response to its ongoing attacks on civilians and civilian infrastructure, both of which contravene international law.

Thus Operation Cast Lead marked a turn in the Palestine solidarity movement in the United States. In addition to the mass public protests seen around the country, chapters of Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) grew with new members and worked with new urgency. Just as it was impossible to defend Israel’s behavior, it also became impossible to ignore the clear and simple call from Palestinian society for the international community to focus on removing its complicity from immoral acts committed against Palestinians.

That spring, UC Los Angeles’ student senate passed a bill condemning the attacks and UC San Diego students offered a bill calling for divestment from companies profiting from the attacks on the Gaza Strip. Although UCSD’s bill did not pass, UC Berkeley students offered a similar bill the next spring. They focused their campus’ attention on the role of American corporations, namely General Electric and United Technologies, in enabling and profiting from violence against Palestinians.

In addition to forcing the question of Palestine onto the forefront of student discussions, the campaign elicited the response of the Israeli government and other “pro-Israel” groups in the United States, who responded by arguing that divestment from General Electric and United Technologies was a form of bigotry against Jewish students.

Israeli Consul General Akiva Tor, who personally attended student government hearings, ceded the point that Israel was engaged in human rights abuses against Palestinians, but argued that Palestinian casualties were a necessary cost for Israel’s security. To complement this justification, Tor repeatedly insisted that, by singling out Israel for scrutiny, the divestment vote would be anti-Semitic.

Anti-divestment talking points found in the room after the hearings revealed that many students had been coached to repeat similar ideas — that divestment was an attack on them as students, that they were being silenced by the bill, and that divestment made them feel unsafe. Certainly many anti-divestment students had strong emotions about the bill, but it also appears that those emotions became the platform for systematic talking points used to change the subject.

Although not offering the same ideological arguments, the UC Regents also sought to discourage divestment by announcing that they would not honor a student vote. Rejecting the proud history of UC divestment from South Africa, the Regents wrote that they would now only consider divestment in the context of genocide, a standard that conveniently upheld actions against Sudan but ruled out the same actions as applied to Israel.

In the face of these pressures, the UC Berkeley student senate nonetheless voted to recommend divestment from General Electric and United Technologies by a 16-4 margin. Unfortunately, senate president Will Smelko vetoed the bill less than a week later and although they had a clear majority, the student senators could not find the supermajority required to override his veto.

This campaign, now captured in the excellent documentary “Pressure Points,” brought the issue of Palestinian rights to the attention of many students who otherwise would be disengaged from the issue. It revealed to many students a lopsided debate in which pro-divestment activists argued the facts while anti-divestment activists ceded facts and argued emotions.

The veto of such a widely supported bill was of course in some days disappointing, but proved to be only a temporary setback. By 2012 a new wave of activism would return divestment to the UC agenda.

A New Year of Activism

Because of the intense repression of student activism on its campus, UC Irvine might be the last place to expect a divestment bill to pass. In 2010, students who had staged a walkout of Israeli Ambassador Michael Oren were arrested and charged by the Orange County District Attorney with conspiracy to disrupt and disrupting a meeting. Also in retaliation, the UC Irvine administration temporarily suspended the Muslim Student Union.

That students could be pursued so aggressively for using a common protest tactic indicates the double standards applied to Palestine activism. While the effect of these prosecutions may have been chilling to some extent, the effect was clearly only temporary.

In November 2012, UC Irvine’s student senate became the first to successfully pass a divestment resolution (without being overturned by veto), voting 16-0 in favor of recommending that the UC system cease investing in a series of companies that enable and profit from every stage of the occupation, supplying Israel not just weapons (e.g. General Electric), but the mechanics and technology it needs to demolish Palestinian homes in the West Bank (Caterpillar), build illegal settlements in their place (Cement Roadstones Holdings), and construct and operate the wall and checkpoint system that strangles Palestinian life (Cemex, Hewlett Packard).

The vote reignited the spirit of 2010, and in the months following it we have seen a series of divestment attempts across the University of California. Although they had submitted a bill every year since 2009, this year’s divestment hearings at UC-San Diego lasted three weeks.

The process became extended when, during the original senate decision, senators who opposed divestment employed a strategy of extending discussion until the building was forced to close at 2 am, so that the bill could not come to a vote.

Other forms of pressure included a senator threatening to resign over the bill, and letters of opposition sent by Representatives Juan Vargas and Susan Davis, as well as the University’s most prominent donor, Irwin Jacobs. Reflecting on the hearings, an SJP board member at UCSD noted that while her group’s earlier efforts were met with justifications of Israeli state policies as security necessities, more recent opposition to divestment focused on emotional issues and attempts to make divestment appear opposed to peace or undermining a two-state solution.

When the vote was finally taken, however, the extensions had proven to only increase the clarity of the issue, and UC San Diego’s government voted for divestment by a much larger margin than activists originally hoped for. They were supported by 16 student organizations, ranging from the Mexican and Chicano Students Association to Asian Pacific Student Alliance, the local chapter of the graduate union, the Black Student Union, and the Coalition of South Asian Peoples.

In response to this tapestry of support, anti-divestment activists reached out for local government figures to send letters of opposition to student senators.

Stanford, Riverside, Santa Barbara, Berkeley, Davis, and Santa Cruz also launched divestment campaigns this spring. Week after week bills were being introduced, debated and voted on at schools across California. The high rate of activism up and down the state has quickly educated and mobilized large numbers of students and has given activists a new sense of what is possible to achieve on campuses.

Although Stanford’s bill was unsuccessful, it received enough support to attract hasty responses from J-Street leader Jeremy Ben-Ami and prominent congressmen such as House Whip Eric Cantor and Democratic Congressman Charles Rangel, who recorded videos urging Stanford not to divest. Riverside’s bill originally passed, but weeks of pressure over the spring break resulted in the senate eventually rescinding the bill.

At Santa Barbara, the process of organizing around the bill produced a list of 30 endorsing groups and beautiful expressions of solidarity across struggles. Moving statements were read by students of color, whose experiences of colonialism, displacement, imperialism and racism were knit together in solidarity with the Palestinian call for divestment.

Support from the UCSB chapter of MEChA and a group of undocumented students was so strong that an undocumented student was appointed to be the sole speaker in favor of the bill at one of its final hearings. It was also reported that after the Campus Democrats voted to endorse the bill in their executive council, alumni issued threats to investigate and possibly strip the chapter of national membership.

Other pressure tactics included the anti-divestment groups claiming to be “Pro-Palestine, Pro-Israel, Pro-Peace, and Anti-Divestment,” an attempt to delegitimize a bill that at the core seeks to remove tuition funds from corporation-supported violence. The bill failed by a small margin on its first vote, partially due to the influence of anti-divestment speakers who employed similar tactics, but was re-introduced twice in May.

At the first re-hearing, anti-divestment senators used procedural loopholes to remove it from the legislative agenda before the meeting officially started. At the second meeting, the bill earned 12 votes to 11 against and 1 abstention. Although the 12-11 result indicated a simple majority, anti-divestment senators argued that the bill needed a majority of the total senate body, and that 12 of 24 total senators failed to pass that mark. The Internal Vice President at first ruled in favor of divestment, but reversed her ruling after being shouted at by an anti-divestment senator until she came to tears.

Other aspects of hostility manifested by anti-divestment activists included sexist speech and threats to students, and a student who punched a wall during the final hearing. While UCSB’s SJP began arranging for carpools to escort pro-Palestine students safely across campus, the administration remained silent about the intense climate of intimidation they faced. The bill now stands in judicial council awaiting review of the final vote.

Building the Debate

At Davis, the bill was prevented from coming to a vote before the full senate, but the campaign itself has created stronger bonds among activists involved in social struggles. Although UC Santa Cruz’s divestment campaign fell a few votes shy of passage (the vote was 17-19-3), students celebrated the remarkable change in campus discourse, evidenced by the fact that the senate’s pro-divestment caucus more than doubled (from 7 to 17 votes) during the three-week deliberation process.

In all, losses in the student senate have not deterred students from continuing to offer bills, because as debates occur across campuses the consensus for Palestinian human rights only continues to grow, and the moral case for divestment becomes more and more clear. Support from allied campus groups, international luminaries (such as Roger Waters, Alice Walker and Angela Davis), and Palestinian students and graduates in the Occupied Palestinian Territory have also been major sources of encouragement for activists.

At UC Berkeley, the re-introduction of a divestment bill carried additional symbolic weight. As at other schools, the years since 2010 debate have been marked by increased pressure against SJP activism and a doubling down on the idea that Jewish students are uniformly “pro-Israel.”

A second setback at Berkeley might have put an indefinite halt to BDS efforts, but in a drawn out senate session that lasted until 5am the next morning, Berkeley’s SJP and allied groups, along with several supportive senators, made eloquent arguments and withstood a series of tactics designed to distract and confuse moderate senators.

These tactics included attempting to insert language into the bill that, if rejected, would make pro-Palestinian activists look unreasonable. One example was the attempt to insert language calling for a two-state solution into the bill. Although “pro-Israel” senators hoped the rejection of this language would show moderates that BDS was truly a one-state movement at its core, the language was voted down and did not achieve the intended result because a broad majority of senators recognized how irrelevant the statehood question is to the issue of Palestinian rights.

Another strategy has been to introduce parallel bills calling for “positive investment,” which have also been seen as efforts to provide centrist senators with a face-saving alternative to voting against divestment. As these efforts to delay and confuse issues were exhausted, the wide array of pro-divestment student voices continued to hold moral sway.

As the Organization of African Students wrote in the Daily Cal, “The decision to support divestment is a result of our concerns about the continued marginalization of Palestinians. As a people with a history of colonization, occupation and human rights violations, we can directly sympathize with the Palestinian people. Some of us have directly experienced such marginalization, and others learned of them from parents or secondary sources. Knowledge of this history makes us opposed to the mistreatment of any group based on physical characteristics, ethnicity or creed.”

By passing the bill, UC Berkeley’s senators affirmed these sentiments and marked the movement’s most significant victory to date.

Confronting Repression

This organizing, however, has not come without facing significant barriers. The repression of Palestine solidarity work at the University of California generally falls into three categories: lawsuits and Title VI complaints made to the Department of Education, attacks on professors and academic programs, and efforts to persuade the University administration to restrict Palestine solidarity work on behalf of “pro-Israel” students. Among these runs the common thread of an argument — that being critical of Israel is the equivalent of being anti-Semitic.

In 2011 one student, Jessica Felber, sued the University of California Berkeley, claiming that its failure to suppress pro-Palestinian activism on campus created a discriminatory environment by denying Jewish students (assumed to all be pro-Israel) equal access to education. On the same theory, UC Santa Cruz lecturer Tammi Rossman-Benjamin filed a complaint against UC Santa Cruz with the U.S. Department of Education.

Both Felber’s lawsuit and Benjamin’s complaint rely on the false theory that criticism of Israel is anti-Semitic. It is also worth noting that both Felber’s lawsuit and Benjamin’s complaint employ, to varying degrees, bigotry against pro-Palestinian students and rank Islamophobia.

Rossman-Benjamin is also implicated, through her organization “AMCHA Initiative,” in attacks on professors who dare to mention Palestine in their work. In 2012, she filed a complaint with the Academic Senate of the University of California, Los Angeles, over Professor David Shorter’s inclusion of Palestine in a course on indigenous movements. Like other administrators who have received her letters, the senate caved to her pressure and reprimanded Shorter, before a follow-up investigation revealed he had done nothing wrong and that Rossman-Benjamin’s group furthermore had no standing to file a complaint.

Last year, AMCHA’s pressure on the UC administration produced a UC-wide letter disingenuously condemning SJP at UC Davis over behavior for which it was not responsible. More recently, video of Rossman-Benjamin using hate speech to describe her campus’ Muslim Stiuent Association and SJP students has led to a new wave of attention on her organization and its role in the campus discourse.

As students protested her remarks, Rossman-Benjamin responded by calling on the UC president to investigate and de-authorize all SJPs and MSAs across the UC system for having ties to terrorist organizations.

Perhaps the most overarching threat to SJP activism and free speech at the University of California has come in the form of the Campus Climate Report process.

In 2010, UC President Mark Yudof commissioned two reports, one for Jewish students and one for Muslim students, which were aimed at addressing each community’s concerns about student experiences.

Yudof’s selection of a politicized leader for the Jewish student report, and his use of Muslims (rather than SJPs) as the parallel report, led to a Jewish report that recommended censorship of Palestine work, while the Muslim report focused on prayer spaces and halal food options and remained largely oblivious to issues relevant to Palestine activists.

The head of the Jewish students’ report, Richard Barton, is the education chair of the Anti-Defamation League, an organization that lobbied against the 2010 Berkeley divestment bill. Shortly after the reports were released, Barton was accused of knowingly excluding testimony of Jewish students critical of Israeli policy and supportive of divestment in order to shape a report that could recommend broad and sweeping restrictions on SJP speech.

Preeminent among Barton’s recommendations is empowering the administration to review and approve or disapprove of SJP’s speakers and events. The report even suggests giving the administration the power to enforce “balance” at these discussions. The reports were met with waves of criticism from Jewish community groups opposed to the report’s methods and conclusions, from scholarly and activist academic organizations, from Jewish students at the University of California, and from free speech groups.

Yet shortly after these recommendations were released, the California state assembly passed HR35, a bill that endorsed the report and its recommendations, going even further by labeling terms like “apartheid” indicators of anti-Semitic speech that should be banned at the University of California.

Reporting by Alex Kane of Mondoweiss later revealed that the UC administration had been consulted throughout the bill’s writing and endorsed its contents until the very last minute, when disagreements over the constitutionality of its final clauses made the administration step back from the bill.

Although UC President Yudof’s endorsement of such a far right wing bill might sound far-fetched, the pattern of his prior behavior — which included openness to pressure from the AMCHA initiative and making statements endorsing the administrative intimidation of students at UC Irvine — goes a long way to explaining this position.

Not long after the bill was passed, the UC Students Association (a council of student elected leader from across the state) rebuked the State Assembly and reaffirmed the right of students to advocate for BDS, including against Israel’s racist and discriminatory behavior. That bold stance was followed by the signatures of over 1,000 UC students and recent graduates.

The U.S. District Court dismissed the Felber v. Yudof case in late 2011. District Judge Richard Seeborg ruled that the First Amendment protected the student protests in question. However, after the complainants re-filed, the UC administration opted to settle the case in a manner that avoided restrictions on student speech. Immediately after the settlement, Felber’s lawyers re-filed their complaint with the Department of Education in the form of a Title VI case.

As of today these threats, the Title VI complaints against UC Santa Cruz, UC Berkeley, and a third against UC Irvine, the Campus Climate Recommendations, and HR35 continue to hang over student activists. There is no clear timetable or indication of when activists will learn about the status of their speech rights, but in some cases the threat of these restrictions is enough to deter some students from becoming active.

Conclusions

What is most interesting when looking at these campaigns is the fact that the anti-divestment crowd’s talking points offered no challenge to the facts provided by Students for Justice in Palestine. That the anti-divestment argument now centers on how divestment will make some students feel indicates that the opposition cannot dispute the claim that Israel is engaged in widespread and systematic human rights abuses in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

The question is no longer whether Israel violates Palestinian rights, but what to do about those violations — a striking indication of just how far public opinion has shifted over the past several years.

Still, the anti-divestment parties on campuses are fighting on two fronts. Some, like the AMCHA Initiative, are trying to shut down debate. On the other hand, many anti-divestment students are employing a discourse of marginalization to re-route debate from issues to emotions. In several cases, it appears that student senates have rejected divestment not on its merits, but in order to avoid being seen as hostile to pro-Israel students.

Anti-divestment students have threatened to drop out of the university should divestment pass, and outside organizations have threatened to tell families not to send students to the university or to send their charitable contributions elsewhere.

But this rhetoric only works as long as “pro-Israel” parties can successfully portray the Jewish community as homogenously supportive of Israeli policies and opposed to divestment. That strategy has recently failed in Britain, where Academic Friends of Israel director Ronnie Fraser failed to win a lawsuit against the University College Union arguing that boycott advocacy was a form of institutional anti-Semitism.

The crux of the case is remarkably similar to the Title VI complaints at the University of California, which also argues that because Jewish students are uniformly supportive of Israel, criticism of its behavior is a form of antagonism towards Jews. The tribunal in that case drew a clear distinction between criticism of Israel and anti-Semitism. The same logic also failed spectacularly in the effort to cancel an open discussion of BDS at Brooklyn College.

Here in California, there are also some signs that this rhetoric is losing traction. The three-year saga of divestment at UC Berkeley not only ended in victory, but also encouraged many Jewish students to re-examine the issue.

After the bill’s passage, Noah Kulwin, a staff writer at the Daily Cal and member of J Street U at UC Berkeley (he opposed the divestment bill), criticized the “pro-Israel” community’s claim that divestment marginalized Jewish students, noting that “for every Jewish student complaining of their ‘marginalization’ on this campus, there is a pro-divestment student with a similar claim that divestment supporters are being painted unfairly as anti-Semitic and that members of our community are trying to whitewash their oppression.” (http://www.dailycal.org/2013/04/25/some-thoughts-on-divestment-and-the-berkeley-jewish-community/)

Later Kulwin expressed sadness when “opponents to divestment attempt to create this illusion that the Jewish community is united on this issue by smearing Jews who support divestment as somehow less relevant and, implicitly, less legitimately Jewish.”

As more students realize that anti-divestment activists employ a double standard in claiming to be silenced while actively silencing others, the power of their rhetoric to scare and slow social justice will only continue to weaken. As more students come to the same conclusions as Kulwin, they may increasingly believe that the anti-divestment crowd does not speak for them. They may also become increasingly critical, either by coming to support Palestinian rights or by deciding that being pro-Israel does not have to mean being pro-Caterpillar.

In the months and years ahead, UC students will likely continue to work for divestment and to raise public awareness about the question of Palestine. Every campaign, regardless of the eventual senate vote, has grown SJP, built solidarity, clarified the issues, and increased public awareness about the everyday consequences of continued occupation and discrimination against Palestinians.

Perhaps UC will continue to oppose and silence students, and perhaps anti-divestment groups will continue to obstruct votes and oppose these bills, but this year SJPs passed a symbolic checkpoint, and the road to justice seems shorter now than before.

July/August 2013, ATC 165

It seems to me that the tactic of anti-divestment groups on campuses to focus on threats to the feelings of (some) Jewish students has far more traction than it should because of decades of attempts by some segments of the “left” to codify “hate speech” and to ban it on campuses. My point is simply that one should consider the possibility that the success of campaigns to censor speech that upsets some groups that have traditionally been subject to discrimination and violence has created an atmosphere that legitimizes the pro-Zionist groups attempts to stigmatize the proponents of BDS.

I am an undergraduate student at UCLA and back in November our school went through this. According to the UC Regents, the measures will have “no power in relation to UC finances.” This was published in a lot of places including the LA Times.

http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-ucla-divestment-israel-20141119-story.html